Bucket Strategy

The bucket strategy is a retirement investment approach that divides a portfolio into three separate segments based on time horizons and risk levels. Each bucket contains assets matched to when funds will be needed: short-term buckets hold safe, liquid investments for immediate expenses, medium-term buckets contain moderate-risk assets for mid-range needs, and long-term buckets focus on growth investments for distant future spending.

The strategy addresses what financial planners call sequence of returns risk (the danger that poor investment performance early in retirement can permanently impair a portfolio's ability to sustain withdrawals throughout retirement). By maintaining separate buckets with different risk profiles, individuals aim to avoid selling growth investments during market downturns while ensuring near-term spending needs remain protected by stable assets.

The bucket strategy has gained popularity among retirement planners and do-it-yourself investors, though it remains subject to debate among financial professionals. Some view it as an effective risk management framework, while others, including prominent financial economists, question its underlying assumptions about long-term stock market safety and argue it may introduce unnecessary complexity compared to traditional balanced portfolios.

This guide explores how the bucket strategy works, the three bucket types, implementation considerations, tax implications, critical perspectives from financial economists, and common questions about this retirement approach.

Key Takeaways

- Bucket strategy divides retirement portfolios into three time-based segments: short-term (1-3 years), medium-term (5-10 years), and long-term (10+ years)

- Short-term buckets hold cash and liquid assets such as savings accounts, money market funds, and certificates of deposit to provide stability for immediate needs

- Medium-term buckets contain moderate-risk investments including intermediate-term bonds and dividend-paying stocks to balance growth with relative stability

- Long-term buckets focus on growth investments such as stock funds and equity portfolios to maximize appreciation potential over extended periods

- Regular rebalancing using waterfall approach involves spending from short-term buckets first, then periodically refilling from medium and long-term buckets

- Social Security and pension income reduce the amount needed in conservative buckets since guaranteed income covers baseline expenses

- Required Minimum Distributions (beginning at age 73 for those born 1951-1959, or age 75 for those born 1960 or later) can complicate bucket management by forcing withdrawals regardless of market conditions or bucket strategy

- Critics argue the strategy may be unnecessarily complex compared to traditional balanced portfolios or target-date funds

- Financial economists question long-term stock safety assumptions underlying the strategy, citing historical data limitations and survivor bias

What Is the Bucket Strategy?

The bucket strategy is a retirement portfolio organization method that segments assets into three distinct categories based on when funds will be needed and the appropriate risk level for each time horizon. Rather than maintaining a single portfolio with one overall asset allocation, the bucket approach separates investments into short-term, medium-term, and long-term buckets, each with different risk characteristics and purposes.

The strategy emerged from retirement planning literature as a framework for addressing the psychological and practical challenges retirees face when managing portfolios during market volatility. The approach gained traction among financial advisors and retirement planners seeking methods to help clients maintain spending discipline during market downturns while preserving growth potential for long-term needs.

The fundamental principle underlying bucket strategy is time horizon matching (aligning investment risk with the timeframe until funds will be needed). Assets required within a few years remain in stable, liquid investments to protect against short-term market fluctuations, while assets not needed for a decade or more can be invested more aggressively to pursue higher returns despite greater volatility.

Bucket strategy differs from traditional retirement portfolio management, which typically maintains a consistent overall asset allocation (such as 60% stocks and 40% bonds) throughout retirement with periodic rebalancing. The bucket approach instead organizes assets by when they will be used rather than by fixed percentage allocations across the entire portfolio.

How the Bucket Strategy Works

Short-Term Bucket (1-3 Years of Expenses)

The short-term bucket typically covers one to three years of living expenses, though some conservative approaches suggest holding up to five years for additional security during extended market downturns. This bucket consists of low-risk, highly liquid assets including cash in savings accounts, money market funds, certificates of deposit, and short-term Treasury securities.

The primary purpose of the short-term bucket is providing stability and ensuring immediate access to funds for regular spending needs. This bucket serves as the source for monthly or quarterly withdrawals to cover living expenses, protecting retirees from the need to sell investments during unfavorable market conditions. The short-term bucket essentially functions as an extended emergency fund specifically designed for retirement spending.

Asset selection for short-term buckets prioritizes capital preservation and liquidity over growth. Investments in this bucket generate minimal returns, often barely keeping pace with inflation, but provide certainty that funds will be available when needed without exposure to market volatility.

Medium-Term Bucket (5-10 Years of Expenses)

The medium-term bucket is designed to cover spending needs approximately five to ten years into the future. This bucket contains conservative to moderate-risk investments including intermediate-term bonds, balanced funds combining stocks and bonds, dividend-paying large-cap stocks, and retirement income funds focused on generating steady returns.

The goal of the medium-term bucket is generating returns that keep pace with or modestly exceed inflation without exposing assets to excessive volatility. This bucket serves as a staging area (assets gradually transition from long-term growth investments into the medium-term bucket, then eventually move to the short-term bucket as spending needs approach).

Investment selection for medium-term buckets balances income generation with moderate growth potential. Assets in this bucket experience some market fluctuation but generally demonstrate less volatility than pure equity investments, providing a middle ground between the safety of short-term holdings and the growth focus of long-term investments.

Long-Term Bucket (10+ Years Until Needed)

The long-term bucket holds assets not needed for at least ten years, emphasizing growth potential over stability. This bucket focuses on higher-risk, equity-oriented investments including domestic and international stock funds, small-cap investments, emerging market equities, and growth-focused mutual funds or exchange-traded funds.

The purpose of the long-term bucket is maximizing portfolio growth over extended periods to ensure assets maintain purchasing power throughout potentially decades-long retirements. This bucket accepts short-term volatility in exchange for the potential for higher long-term returns, operating on the premise that extended time horizons allow recovery from market downturns.

Gains from the long-term bucket are periodically harvested to replenish medium and short-term buckets, ideally during strong market periods to avoid selling at losses. Many bucket strategy practitioners emphasize timing these transfers during market upswings when possible, though extended downturns may necessitate transfers regardless of market conditions.

Implementation Considerations

Customizing Bucket Sizes for Income Sources

Individual bucket sizing depends significantly on guaranteed income sources including Social Security benefits and pension payments. These predictable income streams cover baseline expenses, reducing the amount that must be held in conservative buckets. For example, if Social Security and pension income cover 60% of annual expenses, buckets need only provide the remaining 40%.

Social Security benefits represent inflation-adjusted lifetime income that significantly impacts bucket strategy design. Individuals with higher Social Security benefits relative to expenses can potentially allocate more assets to growth-oriented long-term buckets since guaranteed income reduces dependence on portfolio withdrawals for basic needs.

Healthcare costs require special attention in bucket sizing calculations. Medicare premiums, supplemental insurance, prescription costs, and out-of-pocket medical expenses can represent substantial retirement expenses that vary with age and health status. Conservative bucket sizing often incorporates cushions for healthcare cost escalation, particularly for expenses occurring before Medicare eligibility at age 65.

Required Minimum Distributions beginning at age 73 for those born 1951-1959, or age 75 for those born 1960 or later, complicate bucket management. Federal law mandates annual withdrawals from traditional retirement accounts regardless of spending needs or market conditions, potentially forcing sales of long-term investments during unfavorable periods and creating taxable income that may affect Medicare premiums and Social Security taxation.

Initial Setup Process

Implementing bucket strategy begins with calculating total annual spending needs including essential expenses, discretionary spending, healthcare costs, and periodic large expenditures. This spending baseline determines how much must be held in each bucket to cover expenses during the designated time periods.

Determining bucket sizes involves multiplying annual expenses by the number of years designated for each bucket. Common frameworks suggest one to three years of expenses in the short-term bucket, an additional five to ten years in the medium-term bucket, with remaining assets allocated to long-term growth investments.

Account selection considers which retirement accounts (traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs, 401(k) plans, taxable accounts) will fund each bucket. Tax-advantaged accounts offer benefits but impose restrictions including Required Minimum Distributions and early withdrawal penalties, while taxable accounts provide flexibility but generate annual tax obligations on investment income.

Asset allocation within each bucket requires selecting specific investments appropriate to each bucket's time horizon and risk profile. Short-term buckets might hold 100% cash equivalents, medium-term buckets might contain 50% bonds and 50% dividend stocks, and long-term buckets might hold 80-100% equity investments, though specific allocations vary based on individual risk tolerance.

Ongoing Management and Rebalancing

Bucket strategy requires active management using what practitioners commonly call a "waterfall approach." Regular spending comes from the short-term bucket, which is periodically refilled by transferring assets from the medium-term bucket. The medium-term bucket is then replenished by moving assets from the long-term bucket, ideally during favorable market conditions.

Many investors review buckets annually, assessing whether refilling is necessary and determining optimal timing for transfers from long-term investments. The discipline involves spending exclusively from the short-term bucket while resisting the temptation to tap medium or long-term buckets prematurely, even during market volatility that temporarily reduces long-term bucket values.

Market conditions influence transfer timing decisions. During strong market years, long-term gains can be harvested to replenish other buckets, locking in appreciation and reducing sequence of returns risk. During extended market downturns, individuals may need to temporarily reduce spending, delay transfers from depressed long-term investments, or adjust bucket strategies based on portfolio performance.

This active management requirement distinguishes bucket strategy from more passive approaches. Investors must monitor bucket balances, track market conditions, execute transfers between accounts, and maintain discipline about spending only from designated buckets (responsibilities that may prove challenging during market stress or for individuals preferring hands-off investment approaches).

Tax Implications of Bucket Strategy

Tax consequences of bucket strategy depend primarily on the account types used for each bucket and the frequency of transfers between buckets. Understanding these implications is essential for avoiding unintended tax burdens that could reduce the strategy's effectiveness.

Transfers within the same account type generally create no immediate tax consequences. Moving funds from one investment to another within a traditional IRA, for example, represents a non-taxable exchange. Similarly, reallocating assets within a 401(k) or selling one fund to buy another in the same Roth IRA typically triggers no current taxation.

Transfers between different account types may trigger significant tax obligations. Moving funds from a traditional IRA to a taxable account represents a taxable distribution subject to ordinary income tax and potentially early withdrawal penalties if under age 59½. Converting traditional IRA assets to Roth IRA generates taxable income in the conversion year, though subsequent qualified distributions become tax-free.

Sales of investments in taxable accounts to refill buckets generate capital gains taxes when assets have appreciated. Short-term capital gains (on assets held less than one year) are taxed as ordinary income, while long-term capital gains receive preferential tax rates. Frequent transfers between buckets in taxable accounts may result in ongoing tax obligations that reduce net returns.

Required Minimum Distributions complicate tax planning for bucket strategy. Once individuals reach the applicable RMD age (73 or 75 depending on birth year), federal law mandates annual withdrawals from traditional retirement accounts. These forced distributions may not align with bucket strategy timing preferences and create taxable income regardless of spending needs. Coordinating RMDs with bucket management often requires professional tax planning to minimize overall tax burden.

Tax-loss harvesting opportunities may arise when long-term bucket investments decline in value. Selling depreciated assets in taxable accounts to refill other buckets can generate capital losses that offset other gains or up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually, though wash-sale rules prohibit repurchasing substantially identical investments within 30 days.

Critical Perspectives on Bucket Strategy

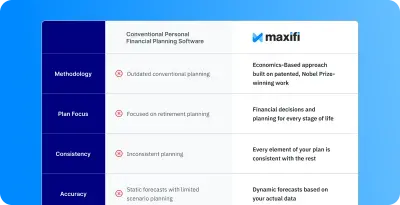

Complexity and Management Burden

Critics of bucket strategy argue the approach introduces unnecessary complexity compared to traditional balanced portfolios. Maintaining three separate buckets with different risk profiles, executing periodic transfers, monitoring multiple time horizons, and coordinating across various account types requires significantly more attention than periodically rebalancing a single portfolio to maintain target allocations.

The additional management burden creates opportunities for implementation errors. Individuals might misjudge appropriate bucket sizes, fail to execute timely transfers, panic during market downturns and abandon the strategy, or struggle with the discipline required to spend only from designated buckets. These behavioral challenges may undermine the strategy's theoretical benefits.

Some financial professionals suggest that simpler approaches (such as traditional balanced portfolios with fixed allocations or target-date funds that automatically adjust risk over time) may achieve similar risk management goals with far less complexity. The question becomes whether the bucket framework's psychological benefits justify the added management requirements.

The Long-Term Stock Safety Debate

Prominent financial economists, including Boston University Professor Emeritus Zvi Bodie and economist Larry Kotlikoff, have challenged the fundamental assumption underlying bucket strategy (that stocks become safer over longer holding periods). This assumption, widely promoted in investment literature, suggests that stock market volatility diminishes over extended time horizons, making equities appropriate for long-term buckets.

Bodie and Kotlikoff argue this premise is flawed. They note that while the probability of positive returns may increase with longer holding periods, the magnitude of potential losses also grows. A portfolio held for 30 years has more time to experience catastrophic declines, and nothing guarantees recovery within any specific timeframe, regardless of historical patterns.

Historical data supporting long-term stock safety suffers from limitations including survivor bias (the tendency to analyze only markets that survived long-term, excluding countries whose stock markets closed due to war, occupation, or regime change). The U.S. stock market's historical success may not be representative of all possible outcomes, and past performance patterns may not continue indefinitely.

The commonly cited statistic that U.S. stocks have never produced negative 30-year returns uses overlapping data periods rather than independent observations, reducing statistical validity. When properly adjusted for inflation, the minimum 30-year real return historically has been approximately 0.5%, far below the substantial gains bucket strategy literature often emphasizes.

International examples challenge long-term stock safety assumptions. The Japanese stock market declined 39% in nominal terms from 1990 to 2020 (a full 30-year period), leaving investors who followed bucket strategy principles with far less than their initial investment. This real-world example demonstrates that multi-decade stock losses can occur in major developed economies, not just theoretical scenarios.

Potential Drawbacks and Limitations

Bucket strategy may reduce overall portfolio returns compared to maintaining consistent asset allocation throughout retirement. By holding significant assets in low-yielding short and medium-term buckets, the approach potentially sacrifices growth that could be achieved through higher equity allocations, particularly during extended bull markets.

The psychological comfort provided by separate buckets may not reflect actual risk reduction. Market downturns affect the entire portfolio regardless of how assets are mentally categorized. A retiree with 60% stocks and 40% bonds faces similar overall portfolio volatility whether organized into buckets or maintained as a unified allocation.

Tax complications from frequent transfers between buckets and accounts can erode returns. Each transfer in taxable accounts potentially triggers capital gains taxes, while movements between retirement account types generate ordinary income taxation. These tax frictions may offset some of the strategy's risk management benefits.

Bucket strategy requires discipline and ongoing attention during precisely the periods when emotional decision-making tends to undermine investment success. During severe market downturns when long-term buckets lose significant value, maintaining the strategy requires confidence that markets will eventually recover (the same confidence required for any equity-heavy retirement approach).

Alternative Approaches to Retirement Portfolio Management

Traditional Balanced Portfolios

Traditional balanced portfolios maintain consistent asset allocations throughout retirement, such as 60% stocks and 40% bonds, with periodic rebalancing when allocations drift from targets. This approach offers simplicity, requires less active management than bucket strategy, and has extensive research support from academic finance literature.

Balanced portfolios automatically buy low and sell high through rebalancing (selling assets that have appreciated above target levels and buying assets that have declined below targets). This disciplined approach captures gains and maintains risk profiles without requiring complex timing decisions about when to transfer between buckets.

Target-Date Funds

Target-date funds automatically adjust asset allocation over time, becoming more conservative as individuals approach and progress through retirement. These funds offer professional management, diversification, automatic rebalancing, and gradually declining risk profiles without requiring individual decision-making about bucket sizes or transfer timing.

Target-date funds provide a single-fund solution that eliminates the need to maintain multiple buckets, coordinate transfers, or make ongoing asset allocation decisions. The gradual risk reduction in target-date funds achieves similar goals to bucket strategy (protecting near-term needs while maintaining growth potential) through a passive, automated approach.

Upside Investing Approaches

Alternative retirement investment strategies, such as the upside investing approach developed by economist Larry Kotlikoff, focus on establishing spending floors based only on safe assets while treating stock investments as pure upside potential. This framework involves calculating baseline living standards assuming stock investments become worthless, then increasing spending only as stocks are gradually converted to safe assets during retirement.

Upside investing avoids sequence of returns risk by never spending from stocks until they have been converted to safe assets. This contrasts with bucket strategy, which treats long-term stock holdings as future spending resources despite ongoing market risk until conversion occurs.

FAQs About Bucket Strategy

Important Considerations

This content reflects retirement planning strategies and investment approaches as of 2025 and is subject to change through legislative action, market condition shifts, or evolving financial planning practices. Required Minimum Distribution ages, tax law provisions, and retirement account rules are adjusted periodically through federal legislation and may differ in subsequent years. The SECURE 2.0 Act established current RMD age requirements that may be modified through future legislation.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment, financial, or tax advice. The information provided represents general educational material about bucket strategy concepts and is not personalized to any individual's specific circumstances. Investment returns, market conditions, tax treatment of portfolio transfers, optimal bucket sizing, and appropriate asset allocations vary significantly based on individual situations. The examples, frameworks, and implementation approaches discussed are for educational illustration only and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's retirement investment decisions. Investment strategies involve risk including potential loss of principal.

Individual retirement investment decisions regarding bucket strategy implementation, bucket sizing, asset allocation, rebalancing frequency, and choice between bucket strategy and alternative approaches must be evaluated based on your unique situation, including age, risk tolerance, income sources, time horizon, tax circumstances, spending needs, guaranteed income from Social Security and pensions, Required Minimum Distribution obligations, and overall financial goals. What may be discussed as common in retirement planning literature may not be appropriate for any specific person. Please consult with qualified financial advisors, tax professionals, and investment specialists for personalized guidance before implementing bucket strategy or making significant retirement portfolio decisions. This educational content does not establish any advisory or investment management relationship.

Disclaimer

This article provides general educational information only and does not constitute legal, tax, or estate planning advice. Beneficiary designations, estate laws, and tax regulations vary significantly by state, account type, and individual circumstances. The information presented here is not intended to be a substitute for personalized legal or financial advice from qualified professionals such as estate planning attorneys, tax advisors, or financial planners. Beneficiary rules are subject to change and can have significant legal and tax implications. Before designating, changing, or making decisions about beneficiaries, you should consult with appropriate professionals who can evaluate your specific situation and applicable state and federal laws.