What Exactly Is Cost Basis?

Cost basis is the original value of an investment for tax purposes, typically what you paid for it plus any fees, commissions, and adjustments. This figure serves as the benchmark for calculating your capital gain or loss when you sell the investment. The basic formula is straightforward: if you sell an asset for more than your cost basis, you have a capital gain subject to taxation. If you sell for less, you have a capital loss that may be deductible.

Cost basis isn't always simply the purchase price. Various events can adjust your basis over time. For example, if you receive additional shares through a stock split, your per-share basis decreases but your total basis remains the same. Reinvested dividends create additional cost basis for new shares purchased. Fees paid to brokers when buying or selling are added to basis. For inherited assets, basis is typically stepped up to fair market value at the date of death. For gifted assets, you generally take on the donor's cost basis. Understanding these adjustments is critical because using an incorrect cost basis can result in overpaying taxes or triggering IRS penalties for underreporting gains.

Does Reinvesting Dividends Change My Cost Basis?

Yes, reinvesting dividends creates a new cost basis for the additional shares purchased. Each reinvested dividend is treated as a new purchase with its own cost basis equal to the amount of the dividend used to buy those shares. This is an important distinction that affects both current and future taxation.

Here's how dividend reinvestment works for tax purposes: When you receive a dividend, you must report it as taxable income in the year received, regardless of whether you take the cash or reinvest it. Dividends are taxed either as ordinary income or as qualified dividends (which receive preferential long-term capital gains rates), depending on holding period requirements and other factors. This taxation occurs whether you pocket the cash or automatically reinvest. When dividends are reinvested to purchase additional shares, those new shares have a cost basis equal to the dividend amount (the market price per share on the reinvestment date). This creates what some call a "double taxation" layer: you pay tax on the dividend when received, then later pay capital gains tax on any appreciation of those reinvested shares when you eventually sell them.

For example, if you receive a $100 dividend and it's automatically reinvested at $50 per share, you purchase 2 new shares with a $50 cost basis each. Years later when you sell those shares for $70 each, you'll pay capital gains tax on the $20 per share appreciation. Proper tracking of reinvested dividend basis is essential to avoid overpaying taxes when you sell. Many investors forget to account for reinvested dividends and end up using only their original purchase price as basis, resulting in higher reported gains and unnecessary tax payments.

Do Stock Splits Affect My Cost Basis?

Yes, stock splits change the cost basis per share but not your total cost basis. The key is understanding that a stock split redistributes your total investment value across more shares, adjusting the per-share basis proportionally while keeping your overall basis unchanged.

When a company executes a stock split, it issues additional shares to existing shareholders according to a specific ratio. In a 2-for-1 split, you receive one additional share for each share owned, doubling your share count. In a 3-for-2 split, you receive three shares for every two previously owned. The market price per share adjusts proportionally, and so does your cost basis per share. For example, if you owned 100 shares with a total cost basis of $5,000 ($50 per share) and the company executes a 2-for-1 split, you now own 200 shares but your total cost basis remains $5,000. Your per-share cost basis becomes $25 ($5,000 total basis ÷ 200 shares). This proportional adjustment means you haven't gained or lost anything economically, just redistributed the same total value across more shares.

Stock splits are non-taxable events, meaning you don't recognize any gain or loss when they occur. However, proper basis adjustment is critical for future tax calculations when you sell shares. Most brokers now automatically adjust the cost basis for stock splits in covered securities, but for noncovered securities acquired before broker reporting requirements, investors must track these adjustments themselves. Reverse stock splits work the same way in reverse: fewer shares with higher per-share basis, but unchanged total basis.

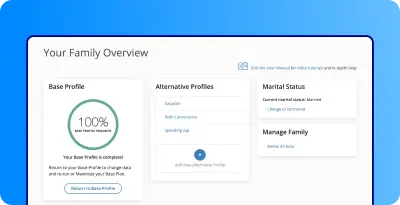

Do Brokers Track Cost Basis for Me?

Yes, brokers are required to track and report cost basis for covered securities, but understanding the distinctions between covered and noncovered securities is essential. Broker reporting requirements were phased in over several years following the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, with different effective dates for different asset types.

Covered securities are those acquired on or after specific dates: January 1, 2011 for stocks and REITs, January 1, 2012 for mutual funds and dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs), and January 1, 2014 for bonds and options. For covered securities, brokers must track adjusted cost basis including adjustments for corporate actions like stock splits, track wash sales within the same account, and report this information to both you and the IRS on Form 1099-B. Noncovered securities are those acquired before these applicable dates. While brokers typically provide cost basis information for noncovered securities to their clients as a courtesy, they are not required to report this information to the IRS, and the responsibility for accurate tracking rests entirely with the investor.

This distinction between covered and noncovered creates practical implications. When you sell investments, your Form 1099-B will separate transactions into covered categories (where the broker reports basis to IRS) and noncovered categories (where you must provide basis). For noncovered securities, if you cannot verify your cost basis, the IRS may assume your basis is zero, meaning you'll owe tax on the full sale amount rather than just the actual gain. Even though brokers track covered securities, maintaining your own records remains important. Broker records may not perfectly capture all adjustments, particularly for securities transferred from other firms or acquired through complex transactions. Keep all purchase confirmations, transfer statements, and documentation of corporate actions affecting your holdings.

How Does Cost Basis Affect Capital Gains Tax?

Your capital gain or loss is calculated as the sale price minus your cost basis, making the basis the critical factor determining your tax liability. The relationship between cost basis and taxes operates on a simple principle: a higher cost basis means a smaller taxable gain (or larger deductible loss), while a lower cost basis means a larger taxable gain.

The tax rate applied to your capital gain depends on your holding period. Short-term capital gains apply to assets held for one year or less and are taxed as ordinary income at your regular tax rates, which range from 10% to 37% depending on your total taxable income. Long-term capital gains apply to assets held for more than one year and benefit from preferential tax rates of 0%, 15%, or 20% depending on your income level. For 2025, the 0% long-term rate applies to taxable income up to $48,350 for single filers and $96,700 for married filing jointly. The 15% rate applies to income between these thresholds and $533,400 (single) or $600,050 (married filing jointly). The 20% rate applies to income above these levels.

Understanding the cost basis allows for strategic tax planning. If you purchased shares at different times and prices, you can use specific identification to choose which shares to sell, potentially selecting higher-basis shares to minimize gains. For example, if you own 100 shares purchased at $50 each and 100 shares purchased at $80 each, and you want to sell 100 shares when the current price is $100, selling the $80-basis shares generates only $2,000 in gains versus $5,000 if you sold the $50-basis shares. This difference could result in hundreds or thousands of dollars in tax savings depending on your tax bracket. Capital losses (where cost basis exceeds sale price) can offset capital gains dollar-for-dollar and can offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually, with excess losses carrying forward to future years.

What Happens If I Don't Know My Cost Basis?

If you cannot verify your cost basis when selling an investment, you face potentially severe tax consequences. The IRS may assume your basis is zero, meaning you'll owe tax on the full sale amount rather than just the actual gain. This can result in significantly overpaying taxes.

This situation commonly arises with old investments purchased decades ago where records have been lost, inherited securities where the decedent's records are unavailable, securities transferred between brokers where basis information wasn't properly transferred, or gifted securities where the donor cannot provide original purchase information. While the IRS position is that zero basis applies when you cannot prove otherwise, there are strategies to reconstruct missing basis information. Start by contacting your broker, as many maintain historical records beyond what appears on statements and may be able to research old transactions. Request old statements from the broker's records retention department. Check with the transfer agent for the security, as they sometimes maintain shareholder purchase history.

For inherited securities, Form 706 (estate tax return) may contain valuation information establishing date-of-death fair market value. For securities held in DRIPs, the plan administrator typically maintains complete purchase history including all reinvested dividends. For very old securities, historical price databases can help establish purchase date pricing if you know approximately when shares were acquired. In cases where no records exist and reconstruction isn't possible, consider consulting a tax professional who may help determine acceptable estimation methods or negotiate with the IRS on reasonable basis determination. Some taxpayers have successfully used average historical prices for periods when purchases likely occurred, though this approach requires careful documentation and IRS acceptance isn't guaranteed. The key lesson: maintain meticulous records of all investment purchases, including confirmation statements, transfer documents, and records of corporate actions like stock splits or mergers. Digital copies stored securely provide backup if paper records are lost.

Can I Adjust My Cost Basis for Fees?

Yes, brokerage fees and commissions from buying or selling investments are included in your cost basis, which reduces your taxable gain. Both purchase-related costs and sale-related costs receive favorable tax treatment by adjusting the basis.

When you purchase investments, costs directly associated with the acquisition increase your cost basis. These include brokerage commissions, transfer taxes, and any other mandatory fees charged by your broker. For example, if you buy 100 shares at $50 each plus a $10 commission, your total cost basis is $5,010 ($5,000 purchase price + $10 commission), giving you a per-share basis of $50.10. When you sell investments, selling costs also adjust your basis calculation. Specifically, selling commissions and fees are subtracted from your sale proceeds rather than added to basis, which has the same tax effect of reducing your gain or increasing your loss. If you sell those same 100 shares for $6,000 but pay a $15 commission, your net proceeds are $5,985, and your taxable gain is $975 ($5,985 proceeds - $5,010 basis) rather than $990 if commissions weren't considered.

With the shift toward commission-free trading at many brokers, direct trading commissions have become less significant for many investors. However, other fees still apply that may adjust basis, including SEC fees, FINRA transaction fees, transfer agent fees for certain transactions, and wire transfer fees when applicable. Not all fees adjust the cost basis. Account maintenance fees, advisory fees, subscription fees for research or data, and fees for services unrelated to specific transactions generally cannot be added to cost basis and may only be deductible as investment expenses if you itemize deductions (subject to significant limitations under current tax law). The distinction matters: fees directly tied to acquisition or sale of specific securities adjust basis and reduce gains, while general account fees receive less favorable tax treatment. When reviewing transaction confirmations, note both the gross amount and net amount to ensure fees are properly captured in your cost basis tracking.

What Is the Difference Between Short-Term and Long-Term Capital Gains?

The distinction between short-term and long-term capital gains hinges on your holding period, the length of time you owned the asset before selling. If you hold an investment for one year or less, gains are short-term and taxed at ordinary income rates ranging from 10% to 37%. If you hold for more than one year, gains are long-term and taxed at preferential rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your income level.

The holding period calculation is precise: you count from the day after the day you acquired the asset up to and including the day you sold it. For example, if you bought stock on March 15, 2024, and sold it on March 15, 2025, you held it for exactly one year (366 days in 2024 being a leap year), qualifying for short-term treatment. Selling one day later, on March 16, 2025, would qualify for long-term treatment since you held it more than one year. This one-day difference can dramatically affect your tax bill. Short-term gains are added to your ordinary income and taxed at your marginal rate. For a taxpayer in the 24% federal bracket, a $10,000 short-term gain incurs $2,400 in federal tax. That same gain as a long-term gain would likely be taxed at 15%, or $1,500, saving $900. For high-income taxpayers in the 37% bracket, the spread is even more dramatic, potentially paying 37% on short-term gains versus 20% on long-term gains.

Strategic timing around the one-year threshold can result in significant tax savings. If you're approaching one year of ownership and are considering selling, evaluate whether waiting a few more days to cross into long-term treatment makes financial sense. However, this must be balanced against market risk; tax savings mean nothing if the investment's value declines while you wait. The holding period rules have some special cases: inherited assets are automatically treated as long-term regardless of how long you or the decedent held them; gifted assets carry over the donor's holding period, so your holding period includes the donor's time; and securities acquired through certain tax-deferred exchanges may have special holding period rules. Short-term and long-term gains are netted separately on your tax return, meaning short-term gains can be offset by short-term losses, and long-term gains by long-term losses, before the two categories are combined.

How Does Gifting or Inheriting Investments Affect Cost Basis?

Gifts and inheritances receive dramatically different basis treatment under tax law, creating vastly different tax consequences for recipients. Understanding these rules is critical for both estate planning and evaluating whether to sell inherited or gifted investments.

For gifted assets, the recipient generally takes a carryover basis, meaning you assume the donor's cost basis and holding period. If your parent bought stock in 1990 for $10,000 and gifts it to you in 2025 when it's worth $50,000, your basis is $10,000 (the donor's original basis). If you later sell for $55,000, you'll pay capital gains tax on the full $45,000 appreciation ($55,000 - $10,000), including appreciation that occurred while your parent owned it. Additionally, your holding period includes your parent's holding period, so the gain would qualify as long-term. There's a special rule when the fair market value at the time of gift is less than the donor's basis: for calculating gains, you use the donor's basis, but for calculating losses, you use the lower fair market value. This prevents gifts from being used to transfer built-in losses. Some gift tax paid on gifts made after 1976 can be added to your basis in proportion to the appreciation at the time of gift, partially offsetting the carryover basis rule.

Inherited assets receive dramatically more favorable treatment through the step-up in basis rule. The basis of inherited property is typically the fair market value on the date of the decedent's death (or an alternate valuation date six months later if elected by the estate). This "step-up" eliminates all unrealized capital gains that accumulated during the decedent's life. For example, if your parent bought stock for $10,000 and it's worth $100,000 at death, your basis as heir is $100,000. If you immediately sell for $100,000, you have zero taxable gain despite the $90,000 appreciation that occurred. This makes inherited assets extremely valuable from a tax perspective. The step-up applies to most assets including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, real estate, and business interests. Inherited assets are automatically treated as long-term for capital gains purposes regardless of how long you or the decedent held them. Some assets don't receive step-up treatment, including retirement accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s), annuities, and certain property received as a gift within one year of death (to prevent deathbed gifting strategies).

Can Cost Basis Apply to Cryptocurrencies?

Yes, cryptocurrencies are treated as property for tax purposes, meaning cost basis rules apply exactly as they do for stocks, bonds, or other capital assets. The IRS established this treatment in Notice 2014-21, issued in 2014, which clarified that virtual currency transactions must follow general tax principles applicable to property transactions.

Your cost basis in cryptocurrency is typically what you paid for it in U.S. dollars, including any fees paid to the exchange or platform. If you purchased 1 Bitcoin for $40,000 including $100 in transaction fees, your cost basis is $40,100. When you sell or exchange the cryptocurrency, you calculate gain or loss as the difference between the fair market value received and your cost basis. Selling that Bitcoin for $45,000 results in a $4,900 gain ($45,000 - $40,100). This gain is short-term if held one year or less (taxed as ordinary income) or long-term if held more than one year (taxed at preferential capital gains rates of 0%, 15%, or 20%).

Cryptocurrency taxation involves some complexities not present with traditional securities. Using cryptocurrency to purchase goods or services is treated as a sale or exchange, triggering taxable gain or loss. If you use Bitcoin worth $45,000 (with $40,100 basis) to buy a car, you recognize a $4,900 capital gain just as if you had sold the Bitcoin for cash. Exchanging one cryptocurrency for another (such as Bitcoin for Ethereum) is a taxable event, not a tax-deferred exchange. Each exchange requires calculating gain or loss. Cryptocurrency received as payment for services is ordinary income equal to the fair market value at receipt, and that fair market value becomes your cost basis. Mining cryptocurrency generates ordinary income equal to the fair market value when mined, establishing your basis in the newly acquired coins.

Cost basis tracking is particularly challenging for cryptocurrency because many investors use multiple exchanges, wallets, and platforms; make frequent small transactions; and lack comprehensive records. Unlike traditional brokers who are required to track and report cost basis for covered securities, cryptocurrency exchanges have historically not provided comprehensive tax reporting, though this is improving. The IRS default method for determining which units are sold is FIFO (first-in, first-out) unless you specifically identify which units you're selling. Given the volatility of cryptocurrency prices, proper basis tracking is essential. Using an incorrect basis can result in significant overpayment or underpayment of taxes. Many investors use specialized cryptocurrency tax software to aggregate transactions across multiple platforms and calculate gains, losses, and basis.