A custodial account is a financial account set up for a minor but managed by an adult. The minor is the legal account holder, but the adult (the custodian) has control of the assets until the account holder reaches adulthood and takes full control.

Custodial accounts are typically set up by families to save for the child's college fees or their first house. The rules on custodial accounts and the age that the account holder takes full control vary by state.

This guide explores custodial account types (UGMA and UTMA), tax treatment under kiddie tax rules, contribution limits and gift tax implications, state-specific age of majority requirements, and key considerations when comparing custodial accounts to 529 plans. Whether evaluating savings strategies for minors or comparing education funding options, understanding these concepts provides essential context for discussions with financial advisors and tax professionals.

Key Takeaways

- Custodial accounts are financial accounts established for minors but managed by adult custodians until the minor reaches the age of majority, typically between ages 18 and 25 depending on state law

- Two primary account types exist: UGMA (Uniform Gifts to Minors Act) accounts hold financial assets like cash, stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, while UTMA (Uniform Transfers to Minors Act) accounts can hold broader asset types including real estate and artwork

- Kiddie tax rules provide tax advantages with the first $1,350 of unearned income tax-free, the next $1,350 taxed at the child's rate (typically 10%), and amounts over $2,700 taxed at the parents' marginal rate for 2025

- Annual gift exclusion allows contributions up to $19,000 per child per year without gift tax consequences for 2025, with amounts above this threshold reducing the contributor's lifetime estate tax exemption

- Assets legally belong to the minor and cannot be reclaimed by parents or custodians, with the child gaining irrevocable control at the state-designated age of majority

- UGMA accounts are available in all 50 states while UTMA accounts are not available in Vermont and South Carolina, which only permit UGMA accounts

- Withdrawals must benefit the minor as custodians can only access funds for expenses directly benefiting the child, such as education, healthcare, or extracurricular activities

- Financial aid implications exist as custodial accounts are assessed as student assets at 20% on FAFSA calculations, compared to parent assets assessed at 5.64%, potentially reducing need-based aid eligibility

- Irrevocable transfers mean permanent gifts as contributions become the child's property immediately upon deposit with no legal mechanism for parents to reclaim control

- Age of majority varies by state with some states offering flexibility to designate ages between 18 and 25, while others specify exact ages such as 18 in Kentucky or 21 in many other jurisdictions

- 529 college savings plans offer alternative benefits with different tax advantages, parental control provisions, and more favorable financial aid treatment compared to custodial accounts

- Multiple contributors can fund accounts with grandparents, relatives, and other adults able to contribute within the annual gift tax exclusion limits of $19,000 per child per year for 2025

What Is a Custodial Account?

A custodial account is a financial account set up for a minor and managed by an adult (the custodian) until the child reaches the age of majority and takes full control. The account is legally owned by the minor from the moment it is established, but the custodian maintains management authority and investment control until the child reaches adulthood according to state law.

Custodial accounts were established under the Uniform Gifts to Minors Act (UGMA) and Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) to provide a straightforward mechanism for transferring assets to minors without the complexity and expense of establishing a formal trust. These accounts allow parents, grandparents, and other adults to make irrevocable gifts to children while maintaining investment control during the child's minority.

The defining characteristic of custodial accounts is that once assets are contributed, they become the permanent property of the child. The custodian cannot reclaim the funds for personal use, though withdrawals are permitted when used for the minor's direct benefit. This irrevocable nature distinguishes custodial accounts from other savings vehicles where parents retain control.

How Custodial Accounts Work

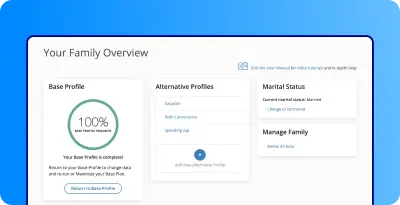

As an adult opening a custodial account for a minor, you can usually set it up with your chosen broker online. Anyone can then contribute. There are two types of account:

- UGMA (Uniform Gifts to Minors Act) accounts can hold cash, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and insurance policies

- UTMA (Uniform Transfers to Minors Act) accounts are less limited and can hold almost any type of asset, including non-financial assets like real estate or artwork

UGMAs are available in all 50 states, whereas UTMAs are not available in Vermont or South Carolina. In both cases, the custodian has the power to buy and sell assets in the account.

The age at which the account holder takes full control varies by state. In most cases, there is some flexibility to choose an age between 18 and 21, or in some cases 25. Other states specify an exact age. In Kentucky, for example, the account holder inherits control at the age of 18.

As a custodian, you can make withdrawals from the account but only for the benefit of the minor in whose name the account has been set up. You can change the custodian through a formal process with your broker.

Tax Treatment of Custodial Accounts

Custodial accounts don't defer tax in the same way as IRAs or 401(k)s, but they do allow you to take advantage of specific tax rules for minors. Minors are subject to 'kiddie tax' rates. For custodial accounts that means:

- The first $1,350 of unearned income in each year is tax-free

- The next $1,350 is taxed at the child's rate, usually 10% (the lowest tax bracket)

- Everything over $2,700 is taxed at the parents' marginal rate

Note that these are limits applying to unearned income. If the child has other forms of unearned income, such as interest and dividends from other sources, that income also counts towards these limits.

As an adult contributing to a custodial account, you can contribute up to $19,000 per child per year without any gift tax implications for 2025. Anything above $19,000 then reduces the portion of your estate that is exempt from federal estate taxes when you die (this amount is $13.99 million per person in 2025, increasing to $15 million on January 1, 2026).

Considerations for Custodial Accounts

As well as the tax advantages (tax rules allow children in 2025 to earn $1,350 tax-free from unearned income), custodial accounts are also flexible. You can pay in as much or as little as you want. Multiple people can contribute and there are no penalties for withdrawing early, as long as the funds are used for the child's benefit.

On the other hand, be aware that a custodial account can affect a child's eligibility for financial aid when it comes to their education. The account is theirs and therefore they can be deemed too wealthy, reducing their financial aid eligibility. In addition, unlike 529 college savings accounts, there is no legal way for parents to take back control of the money. 529 accounts also offer more tax advantages.

FAQs About Custodial Accounts

What Is a Custodial Account?

A custodial account is a financial account set up for a minor and managed by an adult custodian until the child reaches the age of majority and takes full control. The account is legally owned by the minor from the moment of establishment, but the custodian exercises management authority including investment decisions, asset allocation, and withdrawal authorization for the child's benefit. Custodial accounts were created under the Uniform Gifts to Minors Act (UGMA) and Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) to provide a simpler alternative to formal trusts for transferring wealth to children. These accounts are commonly established by parents, grandparents, or other relatives to save for education expenses, down payments on homes, or other significant financial milestones in the child's life. Unlike trust accounts that require legal documents and ongoing administrative expenses, custodial accounts can be opened quickly at most brokerage firms, banks, and financial institutions with minimal paperwork and no setup fees, making them accessible savings vehicles for families seeking to build wealth for minors.

What Can a Custodial Account Be Used For?

Funds in a custodial account can be used for any expense that directly benefits the child, though they cannot be used for general parental obligations or household expenses. Qualifying expenses commonly include educational costs such as tuition, books, tutoring, and school supplies; extracurricular activities including sports equipment, music lessons, and summer camps; healthcare expenses not covered by insurance; clothing and personal items for the child; transportation costs; and technology purchases such as computers or tablets for educational use. The funds cannot be used for basic parental obligations that parents are legally required to provide, such as food, shelter, and basic clothing that would be provided regardless of the account's existence. This distinction means custodial account funds typically supplement rather than replace standard parental support. Importantly, once the child reaches the age of majority and gains control of the account, they can use the funds for any purpose without restriction, including non-educational expenses. Custodians who misuse account funds for personal benefit or non-qualifying expenses may face legal consequences and can be held personally liable for improper withdrawals. Documentation of expenses is commonly recommended to demonstrate proper custodial management.

What's the Difference Between a UGMA and a UTMA Account?

UGMA (Uniform Gifts to Minors Act) accounts can hold financial assets including cash, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, and insurance policies, while UTMA (Uniform Transfers to Minors Act) accounts can hold these same financial assets plus non-financial assets such as real estate, intellectual property, artwork, patents, and royalties. The UGMA was originally enacted in 1956 and subsequently adopted by all 50 states, establishing a uniform framework for transferring financial assets to minors. The UTMA was developed later in 1986 to expand the types of assets that could be transferred to minors, and has been adopted by 48 states. Vermont and South Carolina have not adopted UTMA provisions and only permit UGMA accounts within their jurisdictions. For most families saving through traditional investments such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, the distinction between UGMA and UTMA makes little practical difference. However, families who own real estate, collectibles, or other non-traditional assets and wish to transfer partial ownership to children would require UTMA accounts in states where they are available. Both account types share the same tax treatment under kiddie tax rules and the same irrevocable gift structure, with the primary difference being asset eligibility rather than tax consequences or contribution limits.

When Does the Child Gain Control of the Account?

The age at which the child gains full control of a custodial account varies by state and ranges from 18 to 25 depending on state law and how the account was established. Most states designate age 18 or 21 as the age of majority for custodial accounts, with some states offering flexibility for the custodian to select a specific age within a permitted range when establishing the account. For example, Kentucky mandates transfer at age 18, while many states allow custodians to designate ages 18, 21, or 25 at account opening. A smaller number of states permit delaying transfer until age 25 for UTMA accounts specifically. Once the designated age is reached, the transfer of control is automatic and irrevocable. The now-adult child gains complete authority over the account including investment decisions, withdrawal rights, and beneficiary designation, with no ongoing custodial involvement or parental oversight. This automatic transfer occurs regardless of the child's maturity level, financial responsibility, or current life circumstances, which represents a significant consideration when establishing custodial accounts. Some families find that children at 18 or 21 may not be prepared for substantial financial responsibility, leading many financial planning discussions to favor alternative vehicles such as 529 plans where parental control continues, or trusts where distribution timing can be customized through trust terms.

Can Parents Take Money Back From a Custodial Account?

No, once money is placed in a custodial account, it legally belongs to the child and cannot be reclaimed by parents or custodians for personal use. This irrevocable transfer occurs immediately upon deposit, establishing the minor as the legal owner with all associated property rights. The custodian's authority is limited to managing the account for the child's benefit and making withdrawals only for expenses that directly benefit the minor. Using custodial account funds for personal expenses, household bills, or general family obligations constitutes misappropriation and may result in legal consequences including court-ordered restitution and potential removal as custodian. This irrevocability distinguishes custodial accounts from other savings vehicles such as 529 college savings plans, where the account owner (typically a parent) retains control and can reclaim funds if needed, though potentially with tax consequences. The permanent nature of custodial account gifts also carries estate planning implications, as contributed funds are removed from the contributor's estate for estate tax purposes. While withdrawals for the child's direct benefit are permitted and even expected (for example, paying for private school tuition, medical expenses, or educational enrichment), the funds can never revert to the parent or custodian. This lack of reversibility makes custodial accounts less flexible than alternatives and requires careful consideration of both the amount contributed and the child's anticipated needs before establishing these accounts.

How Are Custodial Accounts Taxed?

Custodial accounts are subject to "kiddie tax" rules, which apply special tax treatment to unearned income received by children. For 2025, the first $1,350 of unearned income (including dividends, interest, and capital gains) is tax-free due to the standard deduction for dependents. The next $1,350 of unearned income is taxed at the child's tax rate, which is typically 10% representing the lowest federal tax bracket. Any unearned income exceeding $2,700 is taxed at the parents' marginal tax rate, which could range from 12% to 37% depending on parental income. These thresholds apply cumulatively to all unearned income the child receives from any source, not just the custodial account, meaning dividends, interest, or capital gains from other accounts also count toward these limits. The kiddie tax was originally designed to prevent high-income parents from shifting investment income to children to take advantage of lower tax brackets. For tax filing purposes, children with unearned income exceeding $1,350 generally must file a tax return using Form 8615 to calculate the kiddie tax, or parents may be able to include the child's income on their own return using Form 8814 if certain conditions are met. It's worth noting that earned income (from wages or self-employment) is taxed at the child's own rates and is not subject to kiddie tax rules. The kiddie tax applies to children under age 18, and in some cases to full-time students under age 24, depending on their earned income and support situation.

Are There Limits on How Much You Can Contribute?

You can contribute up to $19,000 per child per year without any federal gift tax implications for 2025. This amount represents the annual gift tax exclusion, which is adjusted periodically for inflation. Contributions within this limit do not require filing a gift tax return (Form 709) and do not reduce your lifetime gift and estate tax exemption. Multiple people can each contribute up to the annual exclusion amount to the same child in a single year without gift tax consequences, meaning grandparents, parents, and other relatives could each contribute $19,000 to the same custodial account. Married couples can combine their annual exclusions through gift splitting, allowing them to jointly contribute up to $38,000 per child per year. Contributions exceeding $19,000 per person per year are still permitted but require filing Form 709 with the IRS and count against your lifetime gift and estate tax exemption, which is $13.99 million per person in 2025 and increases to $15 million on January 1, 2026. For most families, staying within the annual exclusion amount avoids gift tax filing requirements and preserves the lifetime exemption for larger estate transfers. Unlike retirement accounts such as 401(k) plans or IRAs, custodial accounts have no government-imposed annual contribution limits beyond gift tax considerations, meaning families could theoretically contribute unlimited amounts if willing to utilize lifetime exemption capacity, though such large transfers are uncommon given the irrevocable nature of custodial account gifts.

How Do Custodial Accounts Affect Financial Aid?

Custodial accounts are assessed as student assets rather than parent assets on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which significantly impacts financial aid eligibility. Student assets are assessed at a 20% rate, meaning 20% of the custodial account value is counted as available funds for educational expenses in the Expected Family Contribution (EFC) calculation. By contrast, parent assets are assessed at a maximum rate of 5.64%, making custodial accounts approximately four times more impactful on aid reduction compared to equivalent assets held in parent names. For example, a $20,000 custodial account would increase the EFC by approximately $4,000, potentially reducing financial aid eligibility by a similar amount. This unfavorable treatment continues even if parents serve as custodians, as the legal ownership by the student determines the assessment category. The impact extends across all forms of need-based aid including federal grants, work-study programs, and subsidized loans. Some private colleges using the CSS Profile may assess custodial accounts differently, though typically still less favorably than parent assets. Strategic planning options include spending down custodial accounts on the child's benefit before filing FAFSA (for expenses such as test prep, college application fees, or computers), converting custodial accounts to custodial 529 plans (which are treated more favorably), or deliberately depleting accounts during high school years. Once the child reaches the age of majority and gains control, the account is still assessed as student assets if they remain dependent for financial aid purposes.

Can Custodial Accounts Be Converted Into a 529 Plan?

Yes, UGMA and UTMA accounts can be converted to 529 college savings plans, though the process differs from a direct transfer and involves important tax and ownership considerations. The custodial account assets must first be liquidated (sold), which may trigger capital gains taxes on any appreciation since the original purchase dates. The proceeds are then contributed to a custodial 529 plan established for the same child as beneficiary. Importantly, the 529 remains a custodial account, meaning the child is still the designated beneficiary and this designation cannot be changed to another recipient during their minority. However, once the child reaches the age of majority per state law and gains control of the custodial 529 account, they can subsequently change the 529 beneficiary to a sibling or other qualifying family member. Converting to a custodial 529 plan offers several potential advantages including state tax deductions for contributions in many states, tax-free growth when used for qualified education expenses, and more favorable financial aid treatment (custodial 529 plans are assessed as parent assets at 5.64% rather than student assets at 20% on FAFSA). The decision to convert involves weighing immediate capital gains tax costs against long-term education tax benefits and financial aid implications. If the custodial account has significant unrealized gains, the tax cost of liquidation may be substantial. Conversely, if the account has minimal appreciation or is held at a loss, conversion may be particularly attractive. Financial planning discussions commonly emphasize converting custodial accounts to custodial 529 plans during the beneficiary's childhood to maximize the time period of favorable financial aid treatment and tax-free growth opportunity.

What Happens If the Custodian Dies?

The custodial account remains the child's property if the custodian dies, as the custodian never owns the assets but merely manages them on behalf of the minor. A successor custodian either named in advance when the account was established or appointed by a court will take over management responsibilities until the child reaches the age of majority. Many brokerage firms and financial institutions allow custodians to designate a successor custodian at account opening, providing continuity of management without court involvement. If no successor custodian was designated, state law typically provides that a court will appoint a replacement custodian upon petition, usually prioritizing the surviving parent if one exists, followed by other family members or guardians. The appointment process varies by state but generally requires filing documents with the probate or family court in the jurisdiction where the minor resides. During any gap between the original custodian's death and successor appointment, the account typically remains frozen to protect the minor's assets. The successor custodian assumes all the same fiduciary responsibilities as the original custodian, including the duty to manage assets prudently, maintain accurate records, and use funds only for the minor's benefit. For estate planning purposes, custodians are commonly advised to formally designate successor custodians in advance to avoid delays, court costs, and potential disputes. The custodial account assets are not included in the deceased custodian's estate for estate tax purposes since the custodian never owned the funds, though the obligation to manage the account properly does not terminate until the minor reaches majority or a successor is appointed.

Important Considerations

This content reflects custodial account rules, tax treatment, kiddie tax thresholds, gift tax limits, and state-specific provisions as of 2025 and is subject to change through legislative action, IRS guidance updates, or state law modifications. Kiddie tax thresholds ($1,350/$1,350/$2,700), annual gift exclusion amounts ($19,000), and lifetime estate tax exemptions ($13.99 million in 2025, $15 million starting January 1, 2026) are adjusted periodically based on inflation and may differ in subsequent years. State-specific provisions regarding age of majority, UTMA availability, and custodial transfer rules vary significantly by jurisdiction, with some states offering flexibility in age designation while others mandate specific ages. Vermont and South Carolina do not permit UTMA accounts as of 2025.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, tax, legal, or investment advice. The information provided represents general educational material about custodial account concepts and is not personalized to any individual's specific circumstances. Tax implications vary based on family income, other sources of unearned income, state tax laws, capital gains positions, and overall financial situation. Financial aid calculations depend on individual circumstances including family income, assets, number of children in college, and specific institutional aid policies. Account type selection involves tradeoffs between control, tax benefits, and financial aid impact that differ by family. The examples and calculations discussed are for educational illustration only and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's savings, estate planning, or education funding decisions.

Individual decisions regarding custodial accounts, contribution strategies, account type selection (UGMA vs UTMA vs 529), conversion timing, and education savings approaches must be evaluated based on your unique situation, including income levels, estate planning goals, financial aid considerations, state of residence, family circumstances, child's age and anticipated needs, and comparison with alternative savings vehicles such as 529 plans, Coverdell ESAs, or trust structures. What may be discussed as common in financial planning literature may not be appropriate for any specific person. Please consult with qualified financial advisors, tax professionals, and estate planning attorneys for personalized guidance before establishing custodial accounts, making contribution decisions, or converting between account types. This educational content does not establish any advisory, tax preparation, or legal services relationship.