Your effective tax rate is the actual rate of tax you pay on your income. To be more specific, it's the percentage of your income that you pay in federal income taxes. Typically, that doesn't include other taxes like Medicare, Social Security, and state taxes, or others like sales tax that are unrelated to your income. You might be in the income bracket where you pay a 37% income tax, for example, but a lot of your income is still taxed less than that. The standard deduction for 2025 is $15,750 for single filers ($31,500 for married couples filing jointly), so your effective rate might be lower.

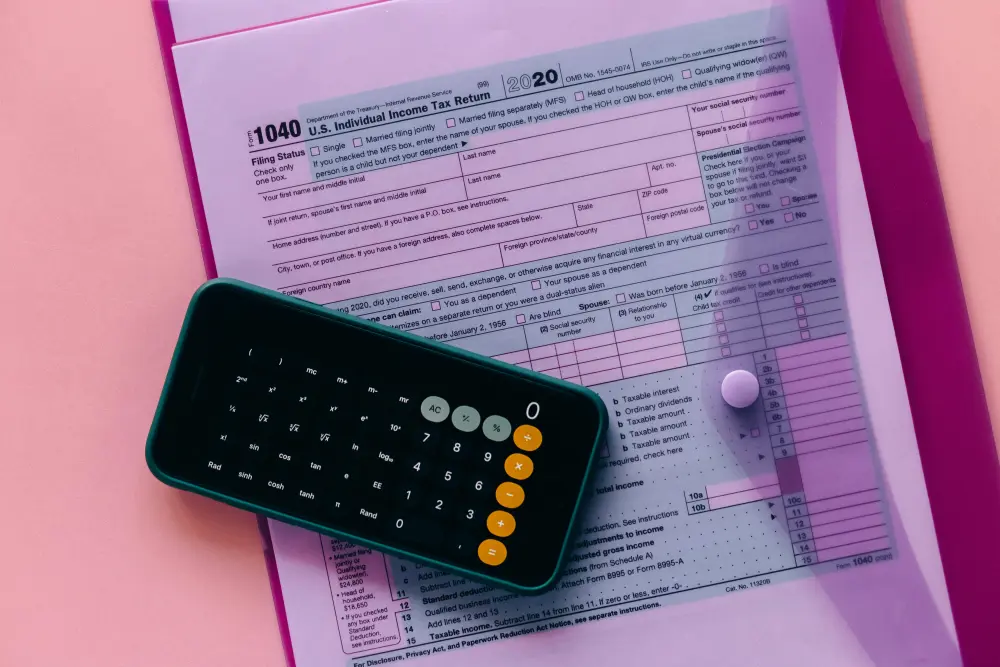

This guide explores how effective tax rate is calculated, how it differs from marginal tax rate, and factors that influence your actual tax burden. Whether evaluating tax planning strategies or understanding your tax obligations, these concepts provide essential context for discussions with tax professionals. Understanding effective tax rate helps individuals assess their true tax burden and make informed financial decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Effective tax rate is the actual percentage of your income that you pay in federal income taxes, calculated by dividing total tax paid by total gross income

- Your effective tax rate and your marginal tax rate are different as marginal tax rate refers to the rate you pay on your last dollar of income while effective rate represents your average rate across all income

- Effective tax rate calculation involves dividing total federal income tax paid by total income from all sources including salaries, investments, capital gains, rental income, and business income

- Standard deduction of $15,750 for single filers in 2025 ($31,500 for married filing jointly, $23,625 for head of household) reduces taxable income before tax calculation

- Progressive tax brackets mean different portions of income are taxed at different rates ranging from 10% to 37%, resulting in effective rates typically lower than top marginal rates

- Tax credits and deductions lower effective tax rate by reducing either taxable income (deductions) or tax owed directly (credits)

- Businesses calculate effective tax rate differently by dividing corporate income tax paid by pre-tax earnings, with the corporate tax rate at 21% for 2025

- Understanding effective tax rate is useful for evaluating true tax burden, comparing tax situations across years, and assessing the impact of tax planning strategies

Effective Tax Rate Definition

Your effective tax rate is the actual rate of tax you pay on your income. To be more specific, it's the percentage of your income that you pay in federal income taxes. Typically, that doesn't include other taxes like Medicare, Social Security, and state taxes, or others like sales tax that are unrelated to your income.

You might be in the income bracket where you pay a 37% income tax, for example, but a lot of your income is still taxed less than that. The standard deduction alone is $15,750 in 2025, so your effective rate might be lower.

How Do You Calculate Your Effective Tax Rate?

To calculate your effective tax rate, start by adding up the total amount that you pay in federal income tax. Then, calculate your total income including:

- Income from salaries

- Investment income and dividends

- Capital gains

- Rental income

- Business or self-employment income

- Interest income

- Any other taxable income (such as bonuses, royalties, or pensions)

Divide your total tax by the total income, multiply it by 100 and you have your effective tax rate.

Effective Tax Rate Example

Let's say you have a total income of $80,000. After the standard deduction of $15,750 for single filers in 2025, that leaves a total taxable income of $64,250. Applying the 2025 tax brackets, you get:

- 10% on the first $11,925 → $1,192.50

- 12% on the next $36,550 ($48,475 − $11,925) → $4,386.00

- 22% on the remaining $15,775 ($64,250 − $48,475) → $3,470.50

Your total federal tax is: $1,192.50 + $4,386.00 + $3,470.50 = $9,049.00

That means your effective tax rate is: $9,049 ÷ $80,000 = 11.3%

How Does Effective Tax Rate Work for Businesses?

Businesses calculate their effective tax rate by taking the total amount that they pay in corporate income tax and dividing that by their total pre-tax earnings. In that case, your business might be subject to a 21% corporate income tax, but after deductions the effective rate could be lower.

What's the Difference Between Effective Tax Rate and Marginal Tax Rate?

Whereas your effective tax rate is the rate of federal income tax you pay overall, your marginal tax rate is the rate of tax you pay on your last dollar of income.

What's the difference? Your effective tax rate is calculated by including all your income and every dollar you pay in federal income tax. Your marginal tax rate, by contrast, is calculated based on the highest rate of tax you pay.

For example, suppose you earn $100,000 a year:

- Your effective tax rate would be approximately 13.5%, since lower portions of income are taxed at 10% and 12% rates, with only a portion reaching the 22% rate, and the first $15,750 isn't taxed due to the standard deduction.

- Your marginal tax rate is 22%, because that's the rate applied to your last dollar of income after accounting for the standard deduction.

Both are still important measures. Your effective tax rate is often the best measure of your overall tax burden, but if you're wondering how much you can expect to take home from any extra income then your marginal rate will likely be a better indicator.

FAQs About Effective Tax Rate

What Is an Effective Tax Rate?

An effective tax rate is the percentage of your total gross income that you actually pay in federal income taxes. It represents your average tax rate across all income, not the highest bracket rate that applies to your last dollar earned. To calculate effective tax rate, divide the total federal income tax you paid by your total gross income from all sources and multiply by 100. For example, if you earned $80,000 and paid $9,049 in federal income tax, your effective tax rate would be 11.3%. This metric differs from your marginal tax rate and provides a more accurate picture of your overall tax burden. Effective tax rate is commonly used in tax planning discussions to evaluate the true impact of income taxes on your finances, compare tax situations across different years, and assess whether tax strategies are reducing your overall tax liability. Understanding your effective tax rate helps provide context for financial planning conversations with tax professionals.

How Is the Effective Tax Rate Different from the Marginal Tax Rate?

The marginal tax rate applies to your last dollar of income, while the effective tax rate is the average percentage you pay across all your income. The United States uses a progressive tax system with seven tax brackets for 2025 ranging from 10% to 37%. Your marginal rate is the highest bracket that applies to any portion of your income. For instance, a single filer earning $100,000 has taxable income of $84,250 after the $15,750 standard deduction, placing them in the 22% marginal tax bracket, meaning their next dollar of income would be taxed at 22%. However, their effective tax rate would be approximately 13.5% because lower portions of income are taxed at just 10% and 12% rates, with only the portion above $48,475 taxed at 22%. The first $15,750 isn't taxed at all due to the standard deduction. The distinction matters for different planning purposes. Effective rate shows your overall tax burden and is useful for year-to-year comparisons. Marginal rate indicates how much tax you'll pay on additional income, making it relevant for evaluating bonuses, raises, or whether to generate additional income. Comprehensive financial planning often considers both rates when evaluating tax strategies.

Does the Effective Tax Rate Include State or Local Taxes?

No, effective tax rate calculations typically include only federal income tax unless specifically stated otherwise. State income taxes, local income taxes, property taxes, and sales taxes are separate from your federal effective tax rate calculation. However, individuals can calculate separate effective rates for state and local taxes using the same methodology of dividing total state or local income tax paid by total gross income. Some states have no income tax (such as Florida, Texas, and Nevada), while others have progressive systems similar to federal taxes, and some use flat tax rates. Combined effective tax rates accounting for federal, state, and local income taxes provide a more comprehensive view of total tax burden. For example, someone with an 11.3% federal effective rate living in a state with a 5% flat income tax would have a combined effective income tax rate of approximately 16.3%. Tax planning discussions commonly reference combined rates when evaluating overall tax obligations, though federal effective rate remains the primary metric referenced in tax literature.

Does the Effective Tax Rate Include Social Security and Medicare?

Usually not. Social Security and Medicare taxes are payroll taxes, not income taxes, so they're typically excluded from effective tax rate calculations. These payroll taxes, collectively known as FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act) taxes, total 7.65% for employees, consisting of 6.2% for Social Security and 1.45% for Medicare. Self-employed individuals pay both the employee and employer portions totaling 15.3%, though they can deduct the employer-equivalent portion. Social Security tax applies only to wages up to $176,100 for 2025, while Medicare tax applies to all wages with an additional 0.9% on high earners. When financial planning materials reference effective tax rate without qualification, they generally mean only federal income tax. However, comprehensive tax burden analyses may calculate a broader effective rate that includes payroll taxes, providing a more complete picture of total tax obligations. For someone earning $80,000, adding the 7.65% FICA rate to an 11.3% effective income tax rate would result in an approximate 18.95% combined effective rate for federal withholdings. Tax planning discussions distinguish between these categories since they're governed by different rules and limitations.

How Can Deductions Affect My Effective Tax Rate?

Deductions reduce your taxable income, which lowers the total tax you pay and therefore reduces your effective tax rate. The most common deduction is the standard deduction, which for 2025 is $15,750 for single filers, $31,500 for married couples filing jointly, and $23,625 for heads of household. Taxpayers can alternatively itemize deductions for expenses including mortgage interest, state and local taxes (capped at $10,000), charitable contributions, and medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of adjusted gross income. For example, a single filer earning $80,000 who takes the $15,750 standard deduction reduces taxable income to $64,250, resulting in federal tax of approximately $9,049 and an effective rate of 11.3%. Without any deduction, the same taxpayer would owe approximately $13,293 in federal tax for a 16.6% effective rate. Above-the-line deductions like traditional IRA contributions, Health Savings Account contributions, and self-employment tax deductions also reduce taxable income. The impact of deductions on effective tax rate varies by income level and tax bracket, with larger deductions producing more substantial reductions in effective rates. Financial planning discussions commonly evaluate how maximizing eligible deductions can lower effective tax rates.

How Do Tax Credits Impact My Effective Tax Rate?

Tax credits reduce your total tax owed directly, which can significantly lower your effective tax rate compared to deductions that only reduce taxable income. Credits are subtracted from your calculated tax liability after applying tax rates to taxable income. Common credits include the Child Tax Credit ($2,200 per qualifying child under 17 for 2025), Earned Income Tax Credit (up to $8,046 depending on income and family size for 2025), education credits like the American Opportunity Credit (up to $2,500) and Lifetime Learning Credit (up to $2,000), and energy efficiency credits for home improvements. Credits can be either refundable or nonrefundable. Refundable credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit can reduce your tax below zero, resulting in a refund, while nonrefundable credits can only reduce tax to zero. For example, a taxpayer with $10,000 in calculated tax who claims $3,000 in credits would pay $7,000, directly reducing their effective tax rate. If that taxpayer earned $80,000, their effective rate drops from 12.5% to 8.75%. Credits have a more powerful impact on effective rates than equivalent deduction amounts since they reduce tax dollar-for-dollar rather than reducing taxable income. Tax planning discussions commonly evaluate credit eligibility and timing to optimize effective tax rates across multiple years.

Do Corporations Calculate Effective Tax Rates the Same Way as Individuals?

Yes, corporations use the same fundamental calculation of dividing total income tax paid by total income, but they divide corporate income tax by pre-tax earnings rather than personal gross income. The federal corporate tax rate is 21% for C corporations as of 2025, established by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. However, corporations rarely pay exactly 21% as their effective rate due to various deductions, credits, depreciation schedules, and tax planning strategies. Large publicly traded corporations often report effective tax rates significantly below the statutory 21% rate, sometimes in the range of 10% to 18%, due to legitimate tax planning and available corporate deductions. Pass-through entities like S corporations, partnerships, and LLCs don't pay corporate-level income tax. Instead, income passes through to owners who report it on personal tax returns and pay at individual rates. For these entities, owners evaluate their personal effective tax rates. Corporate effective tax rates appear in financial statements and earnings reports, providing transparency about tax obligations relative to pre-tax income. Tax policy discussions commonly reference corporate effective rates when evaluating the actual tax burden on businesses compared to statutory rates, with significant variation across industries and company sizes.

Why Is My Effective Tax Rate Lower Than My Tax Bracket?

Your effective tax rate is lower than your top tax bracket because only part of your income is taxed at your highest marginal rate, while the rest is taxed at progressively lower rates. The United States uses a progressive tax system where different portions of income are taxed at different bracket rates. For 2025, single filers pay 10% on income up to $11,925, then 12% on income from $11,926 to $48,475, then 22% on income from $48,476 to $103,350, continuing through seven brackets up to the top 37% rate. Additionally, the standard deduction ($15,750 for single filers in 2025) eliminates tax on that initial amount entirely. For example, someone earning $80,000 might think they're in the 22% bracket, but their effective rate is only 11.3% because $15,750 is deducted, the first $11,925 of remaining income is taxed at just 10%, the next $36,550 at 12%, and only $15,775 at 22%. This progressive structure means effective rates are always lower than marginal rates except for taxpayers in the lowest bracket. The gap between marginal and effective rates widens as income increases because more income is taxed at lower brackets. Understanding this distinction helps individuals avoid overestimating their tax burden and provides context for evaluating additional income opportunities.

How Can I Estimate My Effective Tax Rate for Next Year?

To estimate your effective tax rate for next year, project your total federal income tax liability and divide it by your expected total gross income from all sources. Start by estimating gross income including salaries, bonuses, investment income, dividends, capital gains, rental income, business income, and other taxable sources. Then subtract your expected standard deduction ($15,750 for single filers or $31,500 for married filing jointly in 2025) or itemized deductions if higher. Apply the 2025 tax brackets to your projected taxable income: 10% on the first $11,925, 12% on $11,926 to $48,475, 22% on $48,476 to $103,350, and so forth through the seven brackets. Subtract any expected tax credits such as Child Tax Credit, education credits, or energy credits. Divide the resulting tax by your gross income and multiply by 100 for your estimated effective rate. The IRS provides a Tax Withholding Estimator tool at IRS.gov that can help with these calculations. Comprehensive financial planning software like MaxiFi can model your complete tax situation including multiple income sources, timing of income recognition, deduction optimization, and credit eligibility to project effective tax rates under various scenarios. Estimating next year's effective rate helps with tax planning decisions, withholding adjustments, estimated tax payment calculations, and evaluating whether to defer or accelerate income or deductions between tax years.

Important Considerations

This content reflects federal income tax laws, tax brackets, standard deductions, and effective tax rate calculations as of 2025 and is subject to change through legislative action, regulatory updates, or IRS guidance modifications. Tax brackets, standard deduction amounts, and tax rates are adjusted periodically for inflation and may differ in subsequent years. The 2025 standard deduction amounts reflect increases under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed into law on July 4, 2025. State and local tax rates, which are not included in federal effective tax rate calculations, vary significantly by jurisdiction and change independently of federal tax law.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as tax, financial, or investment advice. The information provided represents general educational material about effective tax rate concepts and is not personalized to any individual's specific circumstances. Tax obligations depend on numerous factors including total income, income sources, filing status, deductions, credits, state residence, and individual tax situation. The examples and calculations discussed are for educational illustration only using simplified scenarios and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's tax planning decisions. Actual tax liability calculations may involve additional complexities including alternative minimum tax, net investment income tax, additional Medicare tax, state income taxes, and various phase-outs of deductions and credits.

Individual tax planning decisions regarding withholding, estimated tax payments, deduction strategies, income timing, and credit optimization must be evaluated based on your unique situation, including current and projected income levels, tax brackets, deductions, credits, investment activities, business income, retirement contributions, and long-term financial goals. What may be discussed as common in tax planning literature may not be appropriate for any specific person. Please consult with qualified tax professionals, certified public accountants, or enrolled agents for personalized guidance before making tax planning decisions or adjusting withholding. This educational content does not establish any tax preparation or advisory relationship.