Pre-Tax

reducing current taxable income while deferring or eliminating tax obligations depending on how funds are ultimately used. This financial term applies across multiple contexts including retirement savings, healthcare spending accounts, commuter benefits, and certain insurance premiums, each with distinct tax treatment rules and future implications.

The strategic value of pre-tax deductions lies in timing: paying less in taxes now by reducing current taxable income, though whether those funds eventually face taxation depends on the account type and usage. Retirement account withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income, while healthcare account distributions may be tax-free for qualified expenses, and commuter benefits provide immediate tax relief without future taxation. Understanding these distinctions enables informed decisions about benefit elections and contribution strategies.

This guide explores the definition of pre-tax as a financial concept, how it functions across different applications, comparisons with after-tax and tax-free treatment, and the tax implications of various pre-tax deductions. Whether evaluating employer benefit options, planning contribution strategies, or understanding paycheck deductions, these educational concepts provide a foundation for discussions with human resources, tax professionals, and financial advisors.

Key Takeaways

- Pre-tax deductions reduce current taxable income by withholding funds before income tax calculations, lowering immediate tax liability

- Applications span retirement, healthcare, and transportation including 401(k)s, FSAs, HSAs, and commuter benefits with distinct rules for each

- Tax deferral differs from tax elimination: retirement accounts face future taxation while healthcare reimbursements may be permanently tax-free

- Pre-tax treatment provides greater upfront savings compared to after-tax contributions since money not paid in taxes remains available for investment or use

- Future tax treatment varies by account type: retirement withdrawals taxed as ordinary income, qualified healthcare expenses tax-free, commuter benefits tax-neutral

- Not all payroll deductions are pre-tax; Roth contributions, charitable donations, and union dues typically processed after-tax

What Does Pre-Tax Mean?

Pre-tax describes money removed from income before tax withholding calculations occur. When employers process payroll, pre-tax deductions are subtracted from gross pay first, establishing a lower taxable wage amount used to determine federal and state income tax obligations. The W-2 form issued annually reflects this reduced taxable income, creating immediate tax savings for the employee.

The mechanism operates through employer payroll systems that process deductions in a specific sequence. Gross pay represents total earnings before any deductions. Pre-tax deductions are subtracted first, creating adjusted gross income subject to federal and state income taxation. However, most pre-tax retirement contributions (401(k), 403(b), traditional IRA) are still subject to Social Security and Medicare (FICA) taxes, which are calculated on gross wages before the retirement contribution deduction. After pre-tax deductions are subtracted, federal income tax and state income tax withholdings are calculated on the reduced amount. This ordering ensures pre-tax deductions provide their intended income tax benefit, though FICA taxes still apply to the full gross amount for retirement contributions.

Tax deferral distinguishes pre-tax from other tax treatments. Deferral means postponing taxation rather than eliminating it entirely. For retirement accounts, this postponement extends until withdrawal, typically decades into the future. For healthcare accounts, funds may never face taxation if used for IRS-qualified expenses. For commuter benefits, the tax advantage occurs at the time of use with no future taxation event.

Consider a simplified example: A professional in Boston or New York earning $175,000 annually who contributes $18,000 to a pre-tax retirement account reports taxable wages of $157,000 on their W-2. In the 24% federal tax bracket, this creates approximately $4,320 in federal tax savings for that year. State and local tax savings add another $900-1,400 depending on jurisdiction (Massachusetts 5%, New York State and NYC combined approximately 8-10%), for total tax savings of approximately $5,220-$5,720. The employee's net paycheck reflects a reduction of approximately $12,280-$12,680 rather than the full $18,000 contribution, making pre-tax savings significantly more affordable than the nominal amount suggests for higher earners. Note: This is a simplified illustration; actual savings vary based on specific marginal tax bracket, state/local rates, and filing status.

How Pre-Tax Works

Payroll Processing Sequence

Employers manage pre-tax deductions through automated payroll systems following IRS regulations. Employees elect deduction amounts during enrollment periods, specifying either fixed dollar amounts or percentages of pay. These elections remain active until changed, creating consistent savings without requiring repeated action. The payroll system processes each paycheck by subtracting pre-tax deductions before federal and state income tax calculations occur. However, for most pre-tax retirement contributions, Social Security and Medicare (FICA) taxes are calculated on the gross amount before the deduction. This distinction is reflected on your W-2: Box 1 (wages subject to federal income tax) shows the reduced amount after pre-tax deductions, while Boxes 3 and 5 (Social Security and Medicare wages) typically show the full gross amount including retirement contributions. The payroll system ensures compliance with tax code requirements and generates proper documentation for year-end reporting.

Tax Calculation Impact

The reduction in taxable income translates directly to lower tax withholding across federal and applicable state income taxes. An employee in the 32% federal bracket who makes a $1,000 pre-tax deduction reduces federal withholding by approximately $320 that pay period. Combined with state and local taxes of 5-8% in markets like Boston or New York, total tax savings reach approximately $370-400, meaning net take-home pay decreases by only $600-630 despite the $1,000 contribution. This mathematical relationship makes pre-tax deductions particularly efficient for higher earners who face elevated marginal tax rates, as the tax savings represent a larger proportion of each dollar contributed.

Account-Specific Tax Treatment

Future taxation depends entirely on account type and usage patterns. Traditional retirement accounts (401(k), 403(b), traditional IRA) accumulate pre-tax contributions and investment earnings that face ordinary income taxation at withdrawal. Healthcare Flexible Spending Accounts provide tax-free reimbursements for qualified medical and dependent care expenses, effectively making pre-tax contributions permanently untaxed. Health Savings Accounts offer triple tax advantages: pre-tax contributions, tax-free growth, and tax-free withdrawals for medical expenses. Commuter benefits deliver immediate tax savings when funds are used for transit or parking without future tax consequences.

Pre-Tax vs After-Tax vs Tax-Free: Understanding Key Distinctions

The following comparison reflects fundamental differences in tax treatment discussed in financial planning education. Individual circumstances determine which approach provides optimal lifetime tax efficiency, and this table is for educational illustration only.

The strategic choice between pre-tax and after-tax contributions depends on comparing current marginal tax rates with anticipated future rates. Someone early in their career expecting significant income growth might favor after-tax Roth contributions, accepting current taxation at lower rates to secure tax-free treatment later when rates may be higher. Conversely, peak earners approaching retirement often prioritize pre-tax contributions to reduce taxation at high current rates, anticipating withdrawals during retirement when income and tax rates decline.

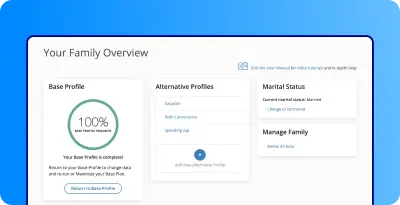

Comprehensive financial planning tools like MaxiFi can model lifetime tax scenarios under different contribution strategies, helping individuals evaluate how pre-tax versus after-tax choices affect long-term financial security across varying income and tax assumptions.

Common Pre-Tax Applications

Retirement Accounts

Traditional 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans represent the most prevalent pre-tax deductions, allowing employees to contribute portions of salary before tax calculation. Traditional IRAs may offer pre-tax treatment through tax deductions when filing returns, though deductibility phases out at higher income levels for those covered by workplace plans. These accounts share common characteristics: contributions reduce current taxable income, investments grow without annual taxation, and withdrawals face ordinary income tax treatment in retirement.

For comprehensive information about contribution limits, catch-up provisions, required minimum distributions, and retirement-specific mechanics, see the detailed Pre-Tax Contributions article.

Healthcare Spending Accounts

Health Care Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs) allow employees to set aside pre-tax dollars for anticipated medical expenses or limited-purpose dental and vision expenses. For 2025, the contribution limit for medical FSAs is $3,300, up from $3,200 in 2024. Health Care FSAs operate on use-it-or-lose-it principles, requiring funds be spent within the plan year, though some employers offer limited carryover amounts ($660 for 2025) or grace periods extending 2.5 months into the following year. Employers may offer either carryover or grace period, but not both.

Dependent Care FSAs operate similarly but with important differences. The 2025 contribution limit is $5,000 for most filers ($2,500 if married filing separately). These accounts cover qualifying childcare and eldercare expenses. Unlike Health Care FSAs, Dependent Care accounts generally cannot offer carryovers under IRS regulations, though some employers may provide grace periods. This distinction is critical for financial planning: Health Care FSA funds may roll forward, while Dependent Care FSA funds typically must be used within the plan year (plus grace period if offered).

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) pair with high-deductible health plans, offering superior tax advantages: pre-tax contributions, tax-free investment growth, and tax-free withdrawals for qualified medical expenses at any age. Unlike FSAs, HSA balances roll over indefinitely with no use-it-or-lose-it restrictions, functioning as supplemental retirement savings vehicles. After age 65, non-medical withdrawals are taxed as ordinary income without penalties, similar to traditional IRAs. The combination of immediate tax deduction, unlimited tax-free compounding, and potential tax-free distribution makes HSAs among the most tax-efficient accounts available.

Commuter and Transit Benefits

Employer-provided commuter programs allow pre-tax deductions for work-related transportation costs including public transit passes, vanpool expenses, and qualified parking near workplaces or transit facilities. The IRS sets monthly limits for these benefits, adjusted annually for inflation. Unlike retirement and healthcare accounts, commuter benefits provide their tax advantage immediately when funds are used for eligible expenses, with no future taxation event. Employees typically receive commuter debit cards or vouchers funded through pre-tax payroll deductions, reducing both income and FICA taxes.

Insurance Premiums and Other Deductions

Group term life insurance premiums for coverage up to $50,000 are generally pre-tax, though amounts exceeding this threshold become taxable income. Health insurance premiums paid through employers often receive pre-tax treatment through Section 125 cafeteria plans. Disability insurance premiums may be pre-tax, though this creates taxable benefit payments if disability occurs—a trade-off some employees strategically avoid by paying premiums after-tax to ensure tax-free disability benefits. Adoption assistance and certain educational assistance programs may qualify for pre-tax treatment within IRS-specified limits.

FAQs About Pre-Tax

Important Considerations

This content reflects general principles of pre-tax deductions as of 2025 and is subject to change through legislative action, IRS regulatory updates, or modifications to tax code provisions. Rules governing pre-tax treatment, contribution limits for various accounts, and qualified expense definitions are adjusted periodically by Congress and federal agencies, and may differ in subsequent tax years depending on inflation adjustments and policy changes.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as tax, financial, or legal advice. The information provided represents general educational material about pre-tax concepts and is not personalized to any individual's specific circumstances. Tax treatment varies based on account type, employer plan design, individual income levels, filing status, state tax laws, and specific usage patterns. The examples, comparisons, and tables discussed are for educational illustration only and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's tax planning or financial decisions.

Individual tax planning and financial decisions regarding pre-tax deductions, account selections, and contribution strategies must be evaluated based on your unique situation, including current and expected future income levels, marginal tax brackets, employment benefits availability, state tax regulations, family circumstances, and specific financial goals. What may be discussed as common in tax planning literature may not be appropriate for any specific person. Please consult with qualified tax professionals, certified financial planners, or employee benefits specialists for personalized guidance before making decisions about pre-tax deductions or benefit elections. This educational content does not establish any advisory, tax preparation, or client relationship.

Disclaimer

This article provides general educational information only and does not constitute legal, tax, or estate planning advice. Beneficiary designations, estate laws, and tax regulations vary significantly by state, account type, and individual circumstances. The information presented here is not intended to be a substitute for personalized legal or financial advice from qualified professionals such as estate planning attorneys, tax advisors, or financial planners. Beneficiary rules are subject to change and can have significant legal and tax implications. Before designating, changing, or making decisions about beneficiaries, you should consult with appropriate professionals who can evaluate your specific situation and applicable state and federal laws.