Salary Deferral

Salary deferral refers to the portion of an employee's earnings voluntarily withheld from current pay and contributed to a qualified retirement plan before taxes are applied. By deferring part of their salary, employees postpone receiving that income until a later date, typically retirement. This arrangement is most common in employer-sponsored plans such as 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b), allowing workers to reduce current taxable income while building long-term financial security through tax-advantaged investment growth.

Understanding salary deferral is essential for evaluating trade-offs between current income and future benefits. Key factors include contribution limits, tax treatment, employer matching policies, and how deferred amounts impact take-home pay. Related terms include pre-tax contributions, Roth deferrals, elective deferrals, and salary reduction agreements.

This guide explores salary deferral operations within employer plans, pre-tax versus Roth differences, contribution limits, and how elections affect payroll and taxation. Whether evaluating benefits packages, adjusting contributions for tax efficiency, or planning retirement withdrawals, understanding these mechanisms supports informed financial decisions.

Key Takeaways

- Salary deferral allows employees to postpone income by directing part of their earnings into qualified retirement plans such as 401(k), 403(b), or 457(b).

- Deferred salary contributions reduce taxable income in the year they are made, helping employees lower current tax liability while saving for retirement.

- Employers often match a percentage of deferred salary, which enhances overall retirement savings and provides an immediate return on the employee's contribution.

- Salary deferral elections are made through payroll systems, ensuring automatic, consistent contributions directly from each paycheck.

- Deferred income grows tax-deferred until it is withdrawn, typically during retirement, when the individual may be in a lower tax bracket.

- The IRS sets annual contribution limits on salary deferrals, with additional catch-up contributions available for workers aged 50 and older.

- For 2025, employees can defer up to $23,500, with catch-up contributions of $7,500 for ages 50+ (total: $31,000) or enhanced catch-up of $11,250 for ages 60-63 (total: $34,750).

- Beginning January 1, 2026, high earners with prior-year FICA wages exceeding $150,000 must make all catch-up contributions as Roth (after-tax) contributions (a new SECURE 2.0 requirement).

- Employees can choose between pre-tax and Roth salary deferrals, determining whether taxes are paid upfront or upon withdrawal.

- Changing a salary deferral percentage generally requires submitting a new election form to the employer or plan administrator, often during open enrollment.

- Excess salary deferrals beyond annual limits can result in double taxation if not corrected by the IRS deadline.

What Is Salary Deferral

Salary deferral is an arrangement between an employee and employer in which a portion of the employee's earnings is withheld from current pay and contributed to a qualified retirement or savings plan, such as a 401(k), 403(b), or 457(b). The deferred portion is excluded from taxable income in the year it is earned and is instead taxed later when the funds are withdrawn, typically during retirement. This approach enables employees to save for the future in a structured, tax-efficient manner while reducing their immediate income tax burden.

From a functional perspective, salary deferrals are part of an employer's payroll system and are governed by IRS regulations. Employees make an elective deferral, choosing how much of their salary to set aside each pay period. Employers then automatically redirect that amount to the retirement plan administrator, who invests it according to the participant's selected options (commonly mutual funds, index funds, or target-date portfolios). This automated process ensures consistency, simplifies saving, and supports dollar-cost averaging through regular contributions.

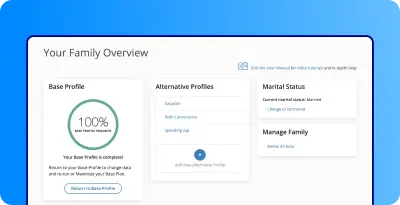

Key participants in a salary deferral plan include the employee (participant), the employer, and the plan administrator. The employer facilitates payroll deductions and may contribute matching funds up to a specified limit. The plan administrator oversees recordkeeping, compliance testing, and investment management. The employee decides contribution levels, investment selections, and whether to make contributions on a pre-tax or Roth (after-tax) basis. These combined roles ensure the plan functions smoothly while complying with both IRS and Department of Labor requirements.

Related terminology includes elective deferral, salary reduction agreement, and deferral election. An elective deferral is the specific dollar amount or percentage of salary the employee chooses to defer. A salary reduction agreement is the formal authorization that permits the employer to withhold those funds. Deferral elections may be changed during open enrollment or after qualifying life events. Together, these elements form the foundation of the salary deferral system, which helps employees build long-term retirement wealth through disciplined and tax-advantaged savings.

How Salary Deferral Works

Eligibility Requirements

Eligibility for salary deferral depends on the type of plan offered and the employer's specific rules. Most full-time employees are eligible to participate in employer-sponsored retirement plans such as 401(k) or 403(b) once they meet minimum service requirements, typically after a set period of employment. Some plans extend eligibility to part-time or seasonal employees, provided they work a minimum number of hours per year. Effective for plan years beginning on or after January 1, 2025, 401(k) and 403(b) plans must allow long-term part-time employees (LTPTEs) who work at least 500 hours in each of two consecutive 12-month periods to make elective deferrals, a reduction from the three-year requirement under SECURE 1.0. This mandatory eligibility expansion ensures more part-time workers can participate in employer-sponsored retirement savings. Employers must follow IRS and ERISA (Employee Retirement Income Security Act) regulations to ensure fair participation and nondiscrimination among employees of all income levels.

Employees must also have earned income to qualify for salary deferrals. For self-employed individuals or business owners, solo 401(k) and SIMPLE IRA plans allow similar pre-tax contribution benefits, functioning as self-directed salary deferrals. Eligibility may also depend on whether the plan offers both pre-tax and Roth options, giving participants flexibility in managing future tax liabilities.

Enrollment and Deferral Election Process

The salary deferral process begins when an employee chooses to participate in the company's retirement plan. Enrollment typically involves the following steps:

- Plan Enrollment: The employee signs up for the employer's retirement plan, often during onboarding or an annual benefits enrollment period.

- Deferral Election: The employee selects a percentage or dollar amount of each paycheck to defer into the plan.

- Salary Reduction Agreement: The employee authorizes payroll deductions by completing a formal election form or online authorization.

- Payroll Deduction and Contribution: The employer automatically deducts the specified amount from gross pay before income taxes are calculated.

- Investment Allocation: The plan administrator invests the funds based on the employee's selected investment options.

This automated process makes saving consistent and effortless, promoting long-term financial discipline. Employees can generally change their deferral rates or investment choices during open enrollment or after qualifying life events, such as marriage or job change.

Beginning January 1, 2025, SECURE 2.0 requires mandatory automatic enrollment for new 401(k) and 403(b) plans established after December 29, 2022. These plans must automatically enroll eligible employees at an initial deferral rate of 3-10% of compensation, with automatic annual increases of 1% up to a maximum of 10-15%. Employees retain the right to opt out within 90 days of enrollment. Important exemptions from this mandate apply to: (1) businesses with 10 or fewer employees, (2) businesses that have been in existence for less than three years, (3) church plans, (4) governmental plans, and (5) SIMPLE 401(k) plans. Plans established before December 29, 2022, are also exempt from the automatic enrollment requirement.

Tax Treatment

The primary advantage of salary deferral is its tax efficiency. For pre-tax contributions, deferred income is excluded from current taxable income, reducing the employee's income tax for that year. Both the contributions and earnings grow tax-deferred until withdrawal, typically after age 59½, when they are taxed as ordinary income.

Alternatively, Roth salary deferrals are made with after-tax dollars. Although they do not reduce current taxable income, qualified withdrawals in retirement are tax-free, provided certain conditions are met (such as holding the account for at least five years). Many employers offer both options, allowing employees to diversify their tax exposure between pre-tax and post-tax savings.

Contribution Limits

The IRS sets annual limits on how much employees can defer each year. For 2025, the elective deferral limit for 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) plans is $23,500. Employees aged 50 and older can contribute an additional $7,500 catch-up contribution (total: $31,000). Employees aged 60-63 may contribute an enhanced catch-up of $11,250 if their plan permits (total: $34,750), a provision effective January 1, 2025, under the SECURE 2.0 Act. Important note for 2026 and beyond: Beginning January 1, 2026, participants whose 2025 FICA wages from the employer sponsoring the plan exceeded $150,000 will be required to make all catch-up contributions (both the standard $7,500 and the enhanced $11,250 for ages 60-63) as Roth (after-tax) contributions. This threshold is indexed annually for inflation from a base amount of $145,000. The mandatory Roth catch-up rule does not apply in 2025; employers should prepare systems during 2025 for good-faith compliance when the rule takes effect in 2026.

Employers may also impose internal limits or restrictions based on payroll frequency or plan type to ensure compliance with nondiscrimination testing.

If an employee contributes to multiple plans across different employers, the total combined deferrals cannot exceed the IRS annual limit. Exceeding these limits can lead to double taxation, as excess deferrals are taxed in both the year contributed and the year withdrawn, unless corrected by April 15 of the calendar year following the excess deferral. For example, 2025 excess deferrals must be corrected by April 15, 2026, to avoid this double-taxation penalty.

Distribution Rules

Funds contributed through salary deferral are intended for long-term retirement savings and generally cannot be withdrawn until the participant reaches age 59½. Distributions are taxed as ordinary income, and early withdrawals typically incur a 10% penalty, unless a qualifying exception applies (such as hardship, disability, or specific medical expenses).

Participants must begin taking Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from pre-tax accounts at age 73 for those born 1951-1959, or age 75 for those born in 1960 or later, as mandated by the SECURE 2.0 Act. The age 75 RMD requirement takes effect January 1, 2033, and applies to participants who attain age 74 after December 31, 2032. Roth deferral accounts, however, are not subject to RMDs during the original owner's lifetime. Understanding these rules helps participants plan withdrawals strategically to minimize taxes and maintain retirement income stability.

For distributions made after December 29, 2025, participants may take penalty-free distributions for qualified long-term care insurance premiums, limited to the lesser of: (a) premiums paid, (b) 10% of vested account balance, or (c) $2,500 (indexed annually). These distributions remain subject to ordinary income tax but avoid the 10% early withdrawal penalty.

Salary Deferral vs. Pre-Tax and Roth Contributions: Key Differences Explained

The following comparison highlights the distinctions commonly discussed in retirement and tax planning between salary deferral, pre-tax contributions, and Roth contributions. Understanding these differences helps employees choose the most tax-efficient way to save for retirement based on their income, goals, and future tax expectations.

Behavioral and Financial Benefits of Salary Deferral

Automatic and Consistent Saving

Salary deferral encourages automatic saving because contributions occur through payroll deductions before employees receive their net pay. This "set it and forget it" approach helps individuals save regularly without having to make active decisions each month. Over time, this consistency fosters financial discipline and helps workers accumulate substantial retirement savings through compound growth.

Reduces Spending Temptation

Because money is redirected to savings before it reaches the employee's checking account, it removes the temptation to spend it elsewhere. Behavioral finance studies often highlight that automatic deferrals create a form of forced saving, helping individuals stay on track even when short-term expenses rise.

Employer Matching Incentives

Salary deferral programs frequently include employer matching contributions, which act as a form of instant return on investment. For example, if an employer matches 50% of the first 6% of salary deferred, the employee gains an immediate 50% boost on that portion. Maximizing the match effectively increases compensation and accelerates retirement readiness.

Long-Term Financial Planning

Salary deferrals also simplify long-term financial planning. By gradually increasing deferral percentages over time (such as using automatic escalation features), employees can align savings growth with pay raises and inflation. This proactive approach ensures future financial security while minimizing the short-term impact on cash flow.

FAQs About Salary Deferral

Important Considerations

This content reflects federal tax laws and retirement plan regulations governing salary deferrals as of 2025 and may be subject to change through legislative amendments, IRS guidance, or updates to employer-sponsored plan rules. Specific elements such as contribution limits, eligibility criteria, and catch-up provisions are reviewed periodically and may differ in future years based on inflation adjustments and federal policy changes, including provisions of the SECURE 2.0 Act effective January 1, 2025.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial, tax, or investment advice. The information provided represents general educational material about salary deferral concepts and is not personalized to any individual's circumstances. Factors such as tax treatment, eligibility, contribution limits, and employer matching provisions can vary across plans. The examples, comparisons, and explanations included are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's financial or retirement decisions.

Individual financial and retirement planning decisions regarding salary deferrals, pre-tax contributions, or Roth options must be evaluated based on each person's unique situation, including income level, tax bracket, employment status, retirement goals, age, state tax laws, and access to employer matching. What may be described as standard in financial planning literature may not be appropriate for every individual. Please consult with a qualified financial advisor, tax professional, or retirement plan specialist for personalized guidance before making contribution or withdrawal decisions. This educational content does not establish any advisory or client relationship.

Disclaimer

This article provides general educational information only and does not constitute legal, tax, or estate planning advice. Beneficiary designations, estate laws, and tax regulations vary significantly by state, account type, and individual circumstances. The information presented here is not intended to be a substitute for personalized legal or financial advice from qualified professionals such as estate planning attorneys, tax advisors, or financial planners. Beneficiary rules are subject to change and can have significant legal and tax implications. Before designating, changing, or making decisions about beneficiaries, you should consult with appropriate professionals who can evaluate your specific situation and applicable state and federal laws.