Will and Testament

A will (formally called a last will and testament) is a legal document that specifies how your property and assets should be distributed after death, names an executor to manage your estate, and can designate guardians for minor children. Unlike a living trust that manages assets during life or a living will that addresses healthcare decisions, a will takes effect only upon death and must go through probate court for validation and enforcement.

Understanding how wills work requires familiarity with state-specific legal requirements, executor responsibilities, probate procedures, and the distinction between assets controlled by a will versus those that pass outside of it through beneficiary designations or trust structures. The decision to create a will, use a trust, or combine both tools depends on factors including estate size, asset complexity, privacy preferences, family circumstances, and probate costs in your state of residence.

Key Takeaways

This guide explores what wills include, legal requirements for valid wills, how wills compare to trusts and other estate planning documents, the probate process, costs of will preparation, and important considerations in estate planning. Whether creating a will for the first time or reviewing existing documents, understanding these concepts provides a foundation for informed discussions with estate planning attorneys.

- A will specifies asset distribution after death, names an executor to manage the estate, and can designate guardians for minor children

- Wills must go through probate court for validation and enforcement, unlike living trusts which avoid probate for properly funded assets

- Valid wills require testamentary capacity (being of sound mind and 18+ years old in most states), written form, proper signature, and witness requirements

- Most states require two witnesses to observe the testator signing the will, though witness requirements vary by jurisdiction

- Wills do not control all assets as retirement accounts, life insurance policies, and jointly owned property with beneficiary designations pass outside the will

- Living trusts and wills serve different purposes, with trusts managing assets during life and avoiding probate while wills provide instructions only after death

- Wills can be updated or revoked at any time during the testator's lifetime through codicils or creating a new will

- Regular will reviews and updates help ensure executor designations remain current, beneficiary information is accurate, and provisions are clear, potentially reducing probate timelines and complications

- Dying without a will (intestate) means state law determines how assets are distributed, who serves as administrator, and asset distribution hierarchy

- Executors have fiduciary duties to inventory assets, pay debts and taxes, and distribute property according to will terms or state intestacy laws

- Self-proving wills with notarized affidavits streamline probate by eliminating the need for witnesses to testify in court

- Online DIY will services range from $39-$349, while attorney-prepared wills typically cost $300-$2,500 for simple documents depending on location and firm size, with complex wills including trusts ranging from $1,000-$5,000 or more

- Many estate plans combine wills and trusts, using trusts for major assets and pour-over wills to transfer remaining assets into the trust

What Is a Will?

A will is a legal document that directs how your property should be distributed after your death, who should manage your estate, and who should care for your minor children if applicable. The formal term "last will and testament" combines two historical concepts: "will" originally referred to real property (land and buildings), while "testament" addressed personal property (possessions and financial assets). Modern usage treats these terms as synonymous, with "will" serving as the standard shortened form.

A will serves several essential functions in estate planning. The document nominates an executor (also called personal representative) who receives legal authority to manage the estate, pay debts and taxes, and distribute assets according to your instructions. For parents of minor children, a will provides the opportunity to name guardians who would care for children if both parents die, though courts make final guardianship determinations based on the child's best interests. The will also allows you to make specific bequests of particular items to particular people, distribute your remaining assets through a residuary clause, and express preferences for funeral arrangements.

The term "testator" refers to the person creating the will. When the testator dies, the will must go through probate, the court-supervised process of validating the document, settling debts, and transferring assets to beneficiaries. This represents a common point of confusion: having a will does not avoid probate but rather provides instructions for how the probate process should proceed. The probate court verifies the will's authenticity, ensures it meets legal requirements, appoints the executor, and supervises the estate administration to protect the interests of creditors and beneficiaries.

Wills take effect only upon death and can be changed or revoked at any time during the testator's lifetime. This flexibility allows you to update your estate plan as circumstances change, such as after marriage, divorce, birth of children, or significant changes in assets or relationships. A will remains a private document during your lifetime but becomes part of the public record once filed with probate court after death, unlike trusts which maintain privacy throughout the process.

Types of Wills

Simple Will

A simple will represents the most common type, appropriate for straightforward estates without complex tax planning needs or complicated family situations. This document distributes assets to named beneficiaries, appoints an executor to manage the estate, and for parents with minor children, names guardians. Simple wills work well when all assets pass to a spouse or are divided equally among children, when no ongoing trusts are needed for beneficiaries, and when estate tax planning is not a concern due to estate size falling below exemption thresholds. Most individuals and couples use simple wills as the foundation of their estate plans.

Pour-Over Will

A pour-over will works in conjunction with a living trust to ensure comprehensive estate planning. This type of will "pours over" any assets not already titled in the trust name into the trust upon the testator's death. Even with careful trust funding, individuals sometimes acquire new assets, receive inheritances, or overlook retitling certain property. The pour-over will acts as a safety net, directing any remaining probate assets into the trust where they are distributed according to trust terms rather than will provisions. These assets must still go through probate before reaching the trust, but the pour-over will ensures consistent distribution according to the trust plan. Estate planning professionals commonly recommend pour-over wills for anyone with a living trust.

Testamentary Trust Will

A testamentary trust will creates one or more trusts upon the testator's death. Unlike living trusts established during lifetime, testamentary trusts come into existence only after death and are created through provisions within the will itself. These trusts commonly serve specific purposes such as holding assets for minor children until they reach a specified age, providing for beneficiaries with special needs without jeopardizing government benefits, protecting assets for beneficiaries who may not manage money well, or achieving specific tax planning objectives. The testator names a trustee in the will who manages trust assets according to the trust terms. Because testamentary trusts are created by will, the estate must go through probate before the trusts are funded and activated.

Self-Proving Will

A self-proving will includes a notarized affidavit signed by the testator and witnesses at the time of will execution. This affidavit serves as sworn testimony that the will was properly executed according to state law requirements. The primary advantage of self-proving wills is streamlining the probate process by eliminating the need for witnesses to appear in court or provide depositions to verify the will's execution. After the testator's death, the notarized affidavit serves as sufficient proof that the will is authentic and was properly executed. Most states recognize self-proving wills, and estate planning attorneys commonly include self-proving affidavits as standard practice when preparing wills. The additional step of notarization when signing the will saves time and potential complications during probate.

Other Will Types

Several other will types exist, though they are less common and may have limited legal recognition depending on state law. Holographic wills are handwritten and signed by the testator without witnesses. Some states recognize holographic wills if the will is entirely in the testator's handwriting, while others do not accept them regardless of circumstances. These wills carry significant risks of being challenged or deemed invalid. Joint wills represent a single document executed by two people, typically spouses, containing the testamentary wishes of both. After one person dies, the survivor generally cannot change the joint will, creating inflexibility that makes this approach generally inadvisable. Mirror wills are separate but substantially identical wills for spouses, each leaving assets to the other and then to the same ultimate beneficiaries. Unlike joint wills, mirror wills allow each spouse to modify their own will. Oral or nuncupative wills consist of spoken testamentary declarations, typically made in imminent peril of death. Most states do not recognize oral wills, and those that do severely limit their application, typically to personal property of minimal value.

Legal Requirements for a Valid Will

Testamentary Capacity

Creating a valid will requires testamentary capacity, meaning the testator must possess the mental ability to understand the nature and effect of making a will. State laws generally establish four elements of testamentary capacity. First, the testator must understand they are making a will and what a will does. Second, they must know the nature and extent of their property, though not necessarily every specific asset or exact values. Third, they must know who their natural heirs are, meaning the people who would typically inherit under state law, such as spouses and children. Fourth, they must understand how the will distributes property among beneficiaries. The testamentary capacity standard is relatively low, requiring only that the testator possess sufficient mental ability at the moment of will execution, even if capacity fluctuates due to illness or medication.

The age requirement for testamentary capacity is 18 years old in most states, though a few states set the minimum at 19. Some states allow younger individuals to make wills in specific circumstances, such as when married or serving in the military. Testamentary capacity represents a lower threshold than the capacity required for many other legal acts. A person may have testamentary capacity even when affected by illness, old age, or mental conditions, provided they understand the four basic elements described above at the time of will execution. However, severe dementia, significant mental illness, or being under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of signing may invalidate a will due to lack of capacity.

Execution Requirements

Valid will execution requires compliance with state-specific formalities designed to prevent fraud and ensure the document truly reflects the testator's wishes. While requirements vary by jurisdiction, most states follow similar patterns. The will must be in writing, whether typed, printed, or in some states, handwritten. Oral wills receive extremely limited recognition. The testator must sign the will, typically at the end of the document, though some states accept the testator's signature anywhere on the document. If the testator cannot physically sign due to disability, most states allow another person to sign on the testator's behalf in the testator's presence and at the testator's direction.

Witness requirements represent the most critical execution formality. Most states require two witnesses, though Vermont requires three. Witnesses must be present when the testator signs the will or when the testator acknowledges an existing signature. The witnesses must understand they are witnessing a will. Witnesses then sign the will themselves, typically in the testator's presence and in each other's presence, though exact requirements vary by state. Witnesses should be "disinterested," meaning they do not receive benefits under the will. If a beneficiary serves as a witness, many states void that person's bequest while leaving the rest of the will valid, though the witness issue creates potential for disputes. Some states require the testator to actually declare to witnesses that the document is their will, while others require only that witnesses observe the signing or acknowledgment.

Self-Proving Affidavits and Notarization

While not required for will validity, a self-proving affidavit significantly streamlines probate. This notarized document, signed by the testator and witnesses simultaneously with will execution, contains sworn statements that the will was properly executed. The affidavit typically states that the testator declared the document to be their will, signed voluntarily while of sound mind and proper age, and that witnesses observed the signing and signed in the testator's presence. When a self-proving will is submitted to probate court, the notarized affidavit serves as sufficient evidence of proper execution, eliminating the need to locate witnesses years later or have them provide testimony or depositions. Most states recognize self-proving wills, and the additional step of notarization when executing the will saves significant time and expense during probate. Estate planning attorneys typically include self-proving affidavits as standard practice when preparing wills.

State Variations and Harmless Error

Will execution requirements vary significantly by state, making it essential to follow the specific rules of your state of residence. States differ in witness requirements, whether notarization is needed, rules for self-proving affidavits, acceptance of holographic wills, and requirements for testator and witness presence. Some states have adopted the "harmless error" or "substantial compliance" doctrine, allowing courts to validate wills with minor execution defects if clear and convincing evidence shows the testator intended the document to be their will. However, not all states recognize harmless error, and relying on judicial discretion to overlook execution defects creates risk and expense. Proper execution following state requirements remains the best practice for ensuring will validity.

What Can a Will Include?

Assets That Can Be Distributed by Will

A will controls the distribution of assets owned solely in the testator's name without other transfer mechanisms. Real property includes homes, land, rental properties, and other real estate titled only in the testator's name. Personal property encompasses vehicles, jewelry, furniture, art, collectibles, clothing, and household items. Financial accounts in the testator's name only, without payable-on-death or transfer-on-death designations, pass through the will. Business interests in sole proprietorships, partnerships, or corporations owned without succession agreements transfer according to will provisions. The residuary clause of a will, which distributes "all the rest, residue, and remainder" of the estate, captures any assets not specifically mentioned, ensuring comprehensive distribution instructions.

Specific bequests allow testators to direct particular items to particular beneficiaries. These provisions might state "I give my diamond ring to my daughter Sarah" or "I give $10,000 to my nephew John." Specific bequests take priority over general distribution provisions. After specific bequests are satisfied and debts and expenses are paid, the residuary clause distributes remaining assets. Estate planning discussions often emphasize the importance of a comprehensive residuary clause to avoid partial intestacy, which occurs when the will fails to dispose of all assets.

Assets That Pass Outside the Will

Many assets transfer to beneficiaries without going through probate or being controlled by will provisions. Understanding which assets bypass the will is fundamental to comprehensive estate planning. Retirement accounts such as 401(k)s and IRAs with named beneficiaries pass directly to those beneficiaries regardless of will provisions. Life insurance policies and pension distributions with designated beneficiaries transfer according to beneficiary designation forms, not will instructions. Property held in living trusts belongs to the trust, not the individual, and passes according to trust terms. Jointly owned property with right of survivorship automatically transfers to the surviving owner. Property owned as tenancy by the entirety, available in some states for married couples, similarly passes to the surviving spouse. Payable-on-death (POD) bank accounts and transfer-on-death (TOD) securities transfer directly to named beneficiaries.

Beneficiary designations override will provisions, making regular review of designation forms essential. Common complications arise when beneficiary forms list an ex-spouse, deceased individual, minor children directly, or "my estate" as beneficiary. Designating "my estate" as beneficiary subjects the asset to probate, eliminating the primary advantage of beneficiary designations. Coordination between beneficiary designations and overall estate planning requires attention to ensure all transfer mechanisms work together to achieve testamentary goals.

Appointments and Other Provisions

Beyond asset distribution, wills serve several other important functions. The executor appointment nominates the person who will manage the estate through probate, though the court makes the final appointment through issuing Letters Testamentary. For parents of minor children, guardian designation represents one of the most important will provisions, expressing preferences for who should care for children if both parents die. While courts make final guardianship determinations based on the child's best interests, judges give significant weight to parental preferences expressed in wills. Some wills also name a property guardian or conservator to manage assets inherited by minor children until they reach age 18, separate from the personal guardian who provides daily care.

Wills can include funeral and burial instructions, though separate documents or pre-arrangements are often more practical since wills may not be located immediately after death. Pet care provisions can designate caretakers and allocate funds for pet care. Charitable bequests allow testators to leave assets or specific dollar amounts to nonprofit organizations. No-contest or in terrorem clauses state that beneficiaries who challenge the will forfeit their inheritance, though enforceability varies by state and such clauses are ineffective against non-beneficiaries. Testators can also include statements explaining reasons for disinheriting someone or making unequal distributions, though such explanations are optional and should be drafted carefully to avoid creating grounds for will contests.

How to Create a Will

Determine What You Own and Who Gets What

The first step in creating a will involves taking inventory of your assets and deciding on distribution. List real estate, vehicles, bank accounts, investment accounts, retirement accounts, life insurance policies, business interests, and valuable personal property. For each asset, consider how it is titled and whether it has beneficiary designations, as these factors determine whether the will controls that asset. Identify who you want to receive your property, considering family members, friends, and charitable organizations. Decide whether you want to make specific bequests of particular items to particular people or prefer to distribute categories of property or percentage shares. Consider contingent beneficiaries in case primary beneficiaries predecease you.

For families with minor children, making guardian decisions represents a critical and often emotional process. Consider factors including who shares your values, who has a relationship with your children, who has the capacity to raise children, and who would be willing to serve. Consider naming alternate guardians in case primary choices cannot serve. Remember that guardian designation expresses your preference but courts make final determinations based on children's best interests.

Choose Your Executor and Consider Other Appointments

The executor manages your estate through probate, making this appointment decision important. Consider who is trustworthy and responsible, capable of handling financial and legal matters, likely to outlive you or be capable when you die, and willing to serve in this role. Executors need not be financial experts but should be organized and able to work with attorneys and accountants. Many people name adult children, spouses, siblings, or trusted friends. Some choose professional executors such as attorneys, accountants, or corporate trustees, particularly for complex estates. Always name alternate executors in case primary choices cannot or will not serve.

If creating testamentary trusts in your will, you'll need to name trustees to manage trust assets. Trustee selection requires evaluating financial competence, trustworthiness, availability for potentially long-term service, and willingness to serve. For parents naming guardians, consider whether to name the same person as property guardian (managing inherited assets) and personal guardian (providing daily care), or to separate these roles.

Decide Between Attorney and DIY Approaches

The decision whether to hire an attorney or use DIY resources depends on estate complexity, comfort with legal documents, state law complexity, and family dynamics. Attorney preparation costs more upfront but provides professional expertise, proper execution supervision, and peace of mind that the will complies with state law. Attorney-prepared wills typically cost $300-$600 for individuals or $500-$1,000 for married couples with simple estates. Complex wills involving testamentary trusts or tax planning cost $1,000-$3,000 or more. Estate planning packages including wills, trusts, powers of attorney, and healthcare directives often cost $1,500-$3,000+.

DIY options include online legal services such as LegalZoom ($99-$349), Nolo Quicken WillMaker software ($99-$139), Rocket Lawyer ($39.99 with membership), and Trust & Will ($199-$299). Free options include state bar association forms, though these provide minimal guidance and no personalization. AARP Foundation offers free will preparation assistance for qualifying seniors in some areas. DIY approaches work well for simple estates with straightforward distribution wishes, but professional review is commonly discussed for complex family situations, significant assets, business ownership, tax planning needs, or uncertainty about legal requirements.

Draft the Will

Whether working with an attorney or using DIY resources, will drafting involves translating your wishes into proper legal language. Attorneys typically conduct interviews to understand your situation, explain options, and draft documents tailored to your circumstances. DIY services use questionnaires to gather information and generate documents based on your responses. Key will components include an opening section identifying you and declaring testamentary intent, revocation of all prior wills, specific bequests of particular items, general bequests of dollar amounts, residuary clause distributing remaining property, executor appointment with powers and compensation, guardian designation if applicable, signature section, and witness attestation section.

Self-proving affidavits, while optional, streamline probate and are commonly included. Carefully review any draft before signing to ensure it accurately reflects your wishes, all beneficiaries are correctly named and identified, executor and guardian choices are correct, and specific bequests are clearly described. Do not sign the will until ready to execute it properly with witnesses and notary if including a self-proving affidavit.

Sign with Proper Witnesses

Proper execution is critical for will validity, and requirements vary by state. Most states require the testator to sign in the presence of two witnesses who must also sign. Some states require the testator to declare to witnesses that the document is their will, while others require only that witnesses observe the signing. Witnesses should be adults (18+ in most states) who are not beneficiaries under the will. If including a self-proving affidavit, the testator and witnesses sign both the will and the affidavit in the notary's presence, and the notary completes the notarization. Never sign the will in advance and later add witness signatures, as this violates execution requirements in most states. All signing should occur in a single session with all necessary parties present.

Attorneys supervise will execution to ensure compliance with state requirements. If using DIY resources, carefully follow state-specific execution instructions. Many online services provide state-specific guidance and forms. Common execution mistakes include wrong number of witnesses, witnesses not present during signing, beneficiaries serving as witnesses, and improper notarization of self-proving affidavits. Such errors may invalidate the will or require witness testimony during probate to prove validity, exactly what self-proving affidavits aim to avoid.

Store Safely and Inform Your Executor

After proper execution, store the original will in a safe, accessible location. Options include a fireproof home safe or file cabinet in a clearly labeled location known to your executor, your attorney's office if they offer document storage, or with the probate court in states offering will deposit services. Avoid bank safe deposit boxes, as access may be restricted after death before probate court authorization. Never store the will in a location where interested parties could destroy or alter it.

Inform your executor where to find the will and provide a copy for their records. Consider providing copies to alternate executors, adult children, or other trusted individuals, though mark copies clearly as "COPY" to prevent confusion about which version is original. Keep a list of where you've distributed copies. Store other estate planning documents such as powers of attorney, healthcare directives, and trust documents together with your will. Maintain a separate document listing the location of important papers, account information, and digital asset access instructions to help your executor manage the estate efficiently.

Updating and Revoking a Will

Wills should be reviewed and potentially updated when life circumstances change significantly. Common triggers for will updates include marriage, which may automatically revoke or partially revoke prior wills in many states, divorce or legal separation, which typically revokes provisions benefiting a former spouse in most states, birth or adoption of children, which may entitle children to inherit even if not mentioned in pre-existing wills through pretermitted heir statutes, and death of a beneficiary, guardian, or executor named in the will. Other circumstances prompting will review include significant changes in assets or financial circumstances, acquisition of real estate in another state, changes in relationships with beneficiaries, move to a different state with different laws, significant changes in estate or tax laws, and general periodic review every three to five years to ensure the will still reflects current wishes.

Two methods exist for modifying a will: creating a codicil or executing a new will. A codicil is a separate document that amends, adds to, or partially revokes provisions of an existing will. Codicils must be executed with the same formalities as wills, requiring proper signature and witnesses. Historically common, codicils are less frequently used today as modern word processing makes creating entirely new wills simple. Multiple codicils can create confusion about which provisions control, making new wills generally preferable.

Creating a new will represents the most common and recommended update method. The new will should include an opening clause explicitly revoking all prior wills and codicils, removing ambiguity about which document controls. The new will must be executed with proper formalities including signature and witnesses. After executing a new will, destroy all copies of the prior will to avoid confusion, though retain records that a prior will existed in case questions arise about your testamentary intent over time.

Revocation can occur through several methods beyond creating a new will with a revocation clause. Physical destruction such as tearing, burning, shredding, or otherwise destroying the will with intent to revoke it accomplishes revocation in most states. Some states require the testator personally to destroy the will, while others allow destruction by another person in the testator's presence and at the testator's direction. Simply crossing out provisions or writing changes on the will does not properly amend it and may create ambiguity about intent. A written revocation statement, executed with will formalities, can revoke a prior will without creating a new one, though this leaves you without any will in place. Marriage often automatically revokes or modifies prior wills in many states, though state laws vary. Divorce typically revokes provisions benefiting a former spouse, treating the will as if the former spouse predeceased the testator, though state laws differ on this treatment.

What Happens Without a Will (Intestacy)

When someone dies without a valid will, the estate undergoes intestate administration and assets are distributed according to state intestacy statutes rather than the deceased person's wishes. The probate court appoints an administrator rather than an executor to manage the estate. Administrators have the same duties as executors but receive appointment based on state statutory priority, typically starting with surviving spouse, then adult children, then parents, then siblings, rather than based on the deceased person's preference.

Intestacy laws follow a predetermined distribution hierarchy that varies by state but generally prioritizes close family members. If the deceased is survived by a spouse and children, distribution depends on whose children they are. Many states give the entire estate to the surviving spouse if all children are children of both the deceased and the surviving spouse. If the deceased has children from other relationships, the spouse typically receives a percentage (often 50%) with children sharing the remainder. If survived by a spouse but no children, the surviving spouse often receives all or most of the estate, though some states allocate a portion to the deceased's parents if living. If survived by children but no spouse, children divide the estate equally. If a child predeceased the deceased but left children (the deceased's grandchildren), those grandchildren typically take their parent's share through representation.

If no spouse or descendants survive, the estate passes to parents if living, then to siblings, then to nieces and nephews, then to more distant relatives following statutory patterns. Each state establishes its own hierarchy for intestate distribution. If no relatives can be identified through the statutory scheme, the estate escheats to the state, meaning the state takes ownership of the property.

Intestacy creates numerous problems compared to having a will. Unmarried partners receive nothing under intestacy laws, regardless of relationship length or interdependence. Stepchildren who were not legally adopted have no inheritance rights. Friends and charities cannot receive anything. The deceased person has no control over who serves as administrator, leading to potential family disputes about appointments. Asset distribution follows state formulas rather than personal preferences, which may not align with the deceased's wishes or family needs. Intestacy offers no opportunity to name guardians for minor children through will provisions, though parents can execute separate guardian designation documents. Specific bequests of meaningful items to particular people cannot be honored. The process often takes longer and costs more than when a clear will directs the proceedings. Despite these disadvantages, many Americans die without wills, leaving families to navigate intestacy laws during an already difficult time.

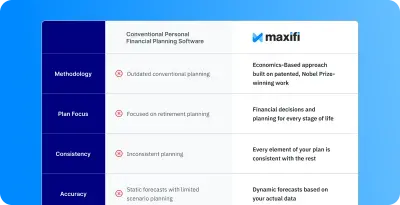

Will vs Trust Comparison

The following comparison reflects common differences between wills and trusts discussed in estate planning education. Individual appropriateness depends on personal circumstances, and this table is for educational illustration only, not personalized recommendations.

Key Differences Between Wills and Trusts

The fundamental distinction between wills and trusts lies in timing and function. A will provides instructions for what happens after death, serving as a set of directions for the probate court to follow. The will remains a private document during your lifetime but becomes public record once filed with probate court. In contrast, a living trust is a legal entity that holds and manages assets during your lifetime and continues after death. You typically serve as trustee of your own revocable living trust during your lifetime, maintaining full control, then a successor trustee distributes assets privately according to trust terms after your death. The trust avoids probate court entirely for assets properly titled in the trust name.

Privacy represents a significant difference. Probate proceedings create public records accessible to anyone, including the will contents, estate inventory with asset values, creditor claims, and beneficiary information. Living trust administration occurs privately without court involvement or public filings. For individuals valuing financial privacy or concerned about family disputes becoming public, trusts offer substantial advantages. Public figures, business owners, and individuals with complicated family situations often cite privacy as a primary reason for using trusts.

Cost comparisons involve tradeoffs between upfront and backend expenses. Wills cost less to create initially, typically $300-$1,000 for attorney preparation of simple wills, while living trusts cost $1,500-$3,000 or more due to greater complexity. However, probate involves court fees, attorney fees, executor compensation, appraisal costs, and publication fees, potentially totaling 2-5% of estate value or more depending on state and complexity. Trust administration after death avoids court costs and typically costs less than probate, though professional trustee fees may apply. The cost-benefit analysis depends on estate size, state probate costs, and asset complexity.

Incapacity planning represents another key distinction. Wills provide no mechanism for managing your affairs if you become incapacitated during life. Separate durable powers of attorney address financial incapacity, and healthcare directives address medical decisions. Living trusts include built-in incapacity planning through successor trustee provisions. If you become unable to manage your affairs, your successor trustee steps in to manage trust assets without court intervention or the need for guardianship proceedings. This seamless transition provides valuable protection, particularly for individuals without family members readily available to serve as agents under powers of attorney.

Many comprehensive estate plans include both wills and trusts rather than viewing them as mutually exclusive options. A common approach involves creating a revocable living trust for major assets such as real estate, investment accounts, and bank accounts to avoid probate on these substantial holdings. A pour-over will accompanies the trust, directing any assets not funded into the trust to pour over into the trust after death, ensuring consistent distribution. The will also names guardians for minor children, something trusts cannot do. This combined approach provides probate avoidance for major assets, privacy, incapacity planning through the trust, and guardian designation through the will.

FAQs About Wills

Important Considerations

This content reflects estate planning and probate laws, will requirements, trust regulations, executor responsibilities, and estate planning costs as of 2025 and is subject to change through legislative action, court decisions, regulatory updates, or policy changes. Will execution requirements including witness rules, age requirements, testamentary capacity standards, notarization requirements, and self-proving affidavit provisions vary significantly by state and are adjusted periodically through state legislation and court rule modifications. Probate procedures, intestacy laws, creditor claim periods, and executor compensation structures differ by jurisdiction. Attorney fees, online service pricing, DIY options, and estate planning costs discussed are current as of 2025 but subject to change based on market conditions, geographic location, and service provider pricing decisions.

This content is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, financial, or tax advice. The information provided represents general educational material about wills, trusts, estate planning concepts, and probate procedures and is not personalized to any individual's specific circumstances. State laws governing wills, trusts, probate, intestacy, guardian appointments, and estate administration vary significantly by jurisdiction, with different requirements for will execution, witness qualifications, testamentary capacity, probate procedures, and intestate distribution hierarchies. The comparison tables, examples, cost ranges, execution procedures, and estate planning strategies discussed are for educational illustration only and do not constitute recommendations for any individual's estate planning needs. Individual circumstances including estate size, asset types, family dynamics, beneficiary needs, state of residence, and specific goals significantly affect whether particular estate planning tools and strategies are appropriate.

Individual estate planning decisions regarding whether to create a will, establish a trust, or use both tools, what provisions to include, who to name as executor or guardian, and how to structure asset distribution must be evaluated based on your unique situation, including estate size and asset composition, family circumstances and beneficiary relationships, state of residence and applicable state laws, privacy preferences and probate cost considerations, incapacity planning concerns, tax implications (estate tax, gift tax, income tax, generation-skipping transfer tax), ownership of real property across multiple states, business interests and succession planning needs, charitable giving intentions, and long-term goals for asset protection and distribution control. What may be discussed as common in estate planning literature may not be appropriate for any specific person. Estate planning and probate involve complex legal, financial, and tax considerations that require professional analysis of your complete situation and coordination among multiple areas of law including family law, tax law, property law, and trust law. Please consult with qualified estate planning attorneys, wills and estates lawyers, tax professionals, and financial advisors for personalized guidance before creating wills, trusts, powers of attorney, healthcare directives, or other estate planning documents. This educational content does not establish any attorney-client, tax preparation, or advisory relationship.

Disclaimer

This article provides general educational information only and does not constitute legal, tax, or estate planning advice. Beneficiary designations, estate laws, and tax regulations vary significantly by state, account type, and individual circumstances. The information presented here is not intended to be a substitute for personalized legal or financial advice from qualified professionals such as estate planning attorneys, tax advisors, or financial planners. Beneficiary rules are subject to change and can have significant legal and tax implications. Before designating, changing, or making decisions about beneficiaries, you should consult with appropriate professionals who can evaluate your specific situation and applicable state and federal laws.